Static Code Analysis of Angular 2 and TypeScript Projects

Edit · Feb 29, 2016 · 17 minutes read · Follow @mgechev

So far, most of the blog posts I’ve written are tutorials; they explain how we can use given technologies, architectures, algorithm etc. For instance:

- Flux in Depth. Store and Network Communication.

- ViewChildren and ContentChildren in Angular 2

- Build Your own Simplified AngularJS in 200 Lines of JavaScript

- Remote Desktop Client with AngularJS and Yeoman

The code for the current research could be found here and here.

The current post is about an exciting project I am working on in my spare time. A few days ago I explained my motivation behind the “Community-drive Style Guide” for Angular 2 that we’re working on. I also mentioned that I am planning to build a configurable static-code analyzer, which makes sure given project follows best practices and contains “correct” Angular 2 code. I called this project ng2lint.

In this article I will explain the main goals of the project, as well as its core challenges and possible solutions. I will also show my current progress. Lets start with the main goals:

Following Style guidelines

We can make sure given project follows some predefined style guidelines by using a standard linting, such as the one introduced by tslint. The Angular 2 Style Guide provides a sample tslint configuration file, which can be used.

As extension of the functionality provided by tslint the ng2linter should introduce file name validation, based on the conventions defined in the style guide.

Following the Best Practices

Although in most cases there’s a good understanding of what best practices are, some of them, especially the ones related to coding style, on big extent depend on personal preferences. This means that a universal static-code analyzer should be configurable.

For instance, according to best practices described in the Angular 2 style guide directives should be used as attributes and components should be used as elements. However, in a legacy project which uses different naming we should be able to bend ng2lint to adjust the project’s specific conventions.

Verifying Program Correctness

By saying correct I mean that the project follows some rules, which are enforced by the Angular framework and without following these rules our Angular application will has a run-time error. Using static code analysis we can verify that:

- All pipes used inside the templates are declared.

- All custom attributes of elements in the templates are declared as either inputs, outputs or directives.

- All identifiers used are inlined in the template expressions exist in the corresponding symbol table (which in the context of Angular is the instance of the component associated to the template).

- etc.

Usage out-of-the box

ng2lint is supposed to work with the current tools provided by the ecosystem that developers use. This means that in order to see warnings in your favorite IDE or text editor you should not be supposed to develop a custom plugin.

Performance

Performance is an important characteristic. In the perfect scenario ng2lint should run its validators for just a few seconds over a big and complex project.

Out of Scope

Since TypeScript is a statically typed language it already provides some extent of type-safety. This means that huge part of the code’s validation is responsibility of the TypeScript compiler. It will slap our hands in case we’ve misspell an identifier name or keyword.

Benefits of ng2lint

Project like this will allow us to receive text editor/IDE warnings for:

- Not following best practices for Angular 2 application development.

- Not following style guidelines our team has agreed upon.

- Incorrect Angular 2-specific code.

Crash Course in Parsing

In order to have better understanding of the up following sections we need to make a quick introduction to parsing, which is core concept in the compiler’s design and implementation.

The input of any compiler is a file which contains a text that needs to be processed. Two top-level goals of each compiler are to:

- Verify whether the input program belongs to the programming language defined with given grammar.

- Execute the program or translate it to a target format.

For our purpose we are interested only in the first goal, which is part of the front-end of the compiler.

Before explaining the challenges and the current results I got in ng2lint, let make a quick overview of how the front-end of a compiler works. The modules we’re going to explain are:

- Lexer

- Parser

Grammars

Grammars allow us to define a set of abstract rules for construction of strings. The set of all strings generated using given grammar is the set of all programs for given programming language. The set of all programs for given programming language is the actual programming language.

This abstract explanation will get more clear in the end of this section. You can read more about context-free grammars here.

Introducing the Lexer

The main purpose of the lexer (a.k.a. tokenizer, scanner) is to take the input character stream and output a stream of tokens. Each token has a “lexeme” which is the actual substring of the program and a “type”.

For instance, lets take a look at the following program:

if (1) {

if (0) {

42 + 12 + 2

}

2 + 3

}

We can implement our parser so it returns an array of JavaScript object, each of which represent an individual token. The first a couple of tokens are going to be:

[

{

lexeme: 'if',

type: 'keyword',

position: {

line: 0,

char: 0

}

},

{

lexeme: '(',

type: 'open_bracket'

position: {

line: 0,

char: 3

}

},

{

lexeme: 1,

type: 'number',

position: {

line: 0,

char: 4

}

},

{

lexeme: ')',

type: 'close_bracket',

position: {

line: 0,

char: 5

}

},

...

]

If you are interested in further reading about lexical analysis I’d recommend you to get familiar with:

Parsing

Now we have a stream of tokens. For a syntax-directed compilers this could be enough. However, in most cases we need to build an intermediate representation of the program which brings more semantics and is easier to process by the back-end of the compiler. As input for creating this intermediate representation the parser uses the token stream we got from the lexer and the grammar associated to the programming language.

The process of developing lexers and parsers usually contains the same repetitive steps across compilers for different languages so that is why there are tools which allow you to generate the code for these two modules based on given grammar.

Deep-dive in parsing is out of the scope of the current article but lets tell a few words about the basics. What is this “intermediate representation” that the parser builds based on the token stream and the language’s grammar? Well, it builds a tree, more accurately an abstract syntax tree (AST).

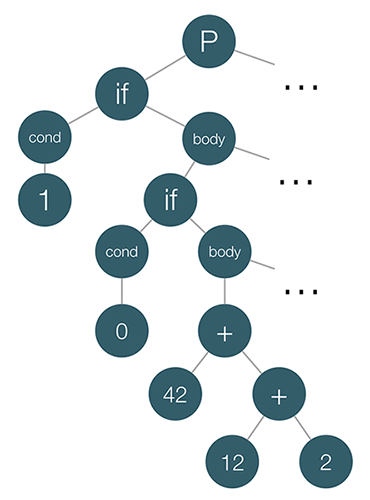

Lets take a look at the AST of the program above:

In case you’re interested in further reading about parsers, take a look at the following resources:

One more step…

We’re almost done with the theory behind ng2lint. In this final step of the “Crash Course in Parsing” we will just peek at the back-end of any compiler by introducing a classical design pattern which is exclusively used there.

In object-oriented programming and software engineering, the visitor design pattern is a way of separating an algorithm from an object structure on which it operates.

How we can use this pattern in order to interpret the program we defined above, using its intermediate AST representation? We want to have different algorithms for processing the AST, for instance:

- Interpretation of the AST

- Code generation

- Static code analysis

This means that the visitor pattern is perfect for this purpose - we will develop an algorithm for processing the AST but we won’t couple it with any of these algorithms.

Here’s how we can develop a visitor for this purpose:

class InterpretationVisitor {

execute(ast) {

ast.statements.forEach(this.visitNode.bind(this));

}

visitNode(node) {

switch (node.type) {

case 'if_statement':

return this.visitIfStatement(node);

break;

case 'expression':

return this.visitExpression(node);

break;

default:

throw new Error('Unrecognized node');

}

}

visitIfStatement(node) {

if (this.visitNode(node.condition)) {

node.statements.forEach(this.visitNode.bind(this));

}

}

visitExpression(node) {

if (node.operator) {

return this.visitNode(node.left) + this.visitNode(node.right);

}

return node.value;

}

}

Now all we have to do in order to interpret the program is:

let visitor = new InterpretationVisitor();

visitor.execute(root);

tslint for instance, uses similar approach for the implementation of the rules it provides.

Lets peek at a sample rule definition:

import * as ts from 'typescript';

import * as Lint from '../lint';

export class Rule extends Lint.Rules.AbstractRule {

public static FAILURE_STRING = "type decoration of 'any' is forbidden";

public apply(sourceFile: ts.SourceFile): Lint.RuleFailure[] {

return this.applyWithWalker(<Lint.RuleWalker>(new NoAnyWalker(sourceFile, this.getOptions())));

}

}

class NoAnyWalker extends Lint.RuleWalker {

public visitAnyKeyword(node: ts.Node) {

this.addFailure(this.createFailure(node.getStart(), node.getWidth(), Rule.FAILURE_STRING));

super.visitAnyKeyword(node);

}

}

In the snippet above we have definition of two classes:

Rule-tslintuses TypeScript’s compiler for generation of the AST of each file in given project. Once the AST is available,tslintpasses it to theapplymethod of each rule.NoAnyWalker- a visitor which extends theRuleWalkerclass that provides some features, such ascreateFailure,addFailure, etc. TheNoAnyWalkeroverrides the definition of thevisitAnyKeywordmethod and reports a failure once it finds “anydecorations”.

For instance:

let foo: any = 32;

Will fail with type decoration of 'any' is forbidden.

Challenges in ng2lint

Now lets take a look at the goals we defined earlier and see how we can take advantage of already know in order to achieve them.

Usage out-of-the box

The way to achieve this goal is to reuse the error reporting mechanism of existing, popular tool. tslint is already widely supported by most IDEs and text editors that are popular in the Angular’s community. If ng2lint uses its error reporting mechanism the IDEs/text editors that support tslint will support ng2lint as well.

Following Style guidelines & Following the Best Practices

We can achieve this goal by using tslint as well. Verifying that given source file follows defined style guidelines involves static code analysis similar to the one performed by the rules declared by tslint and the ones developed by the community.

Verifying Program Correctness

This is the most challenging part of ng2lint because of the following reasons:

- TypeScript does not parses the Angular 2 templates.

- There is extra semantics on top of TypeScript introduced by Angular 2.

- There are externalized templates which need to be loaded from disk.

- There are definitions of directives and components which need to be resolved.

- The process is slow so parsing should be performed only over the changed code.

Lets discuss approaches for handling some of these challenges.

TypeScript does not parses the Angular templates

Suppose we have the following component definition:

@Component({

selector: 'custom-heading',

template: '<h1>{{heading}}</h1>'

})

class CustomHeadingComponent {

heading = 42;

}

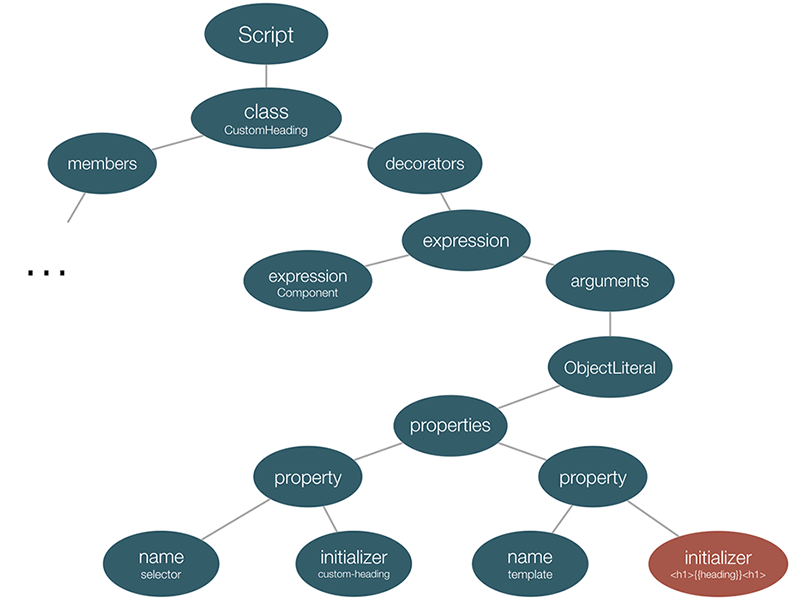

Once TypeScript’s compiler parses Angular program the AST will look something like:

Notice the red node in the bottom-right - it is the initializer of the second key-value pair from the object literal that we pass to the @Component decorator.

Since it is not responsibility of TypeScript to parse Angular’s templates it only holds their string representations, or in case of templateUrl their paths.

Fortunately, Angular 2 exposes its TemplateParser. Thanks to Angular’s platform agnostic implementation and parse5, TemplateParser could be used in node environment.

It allows us to parse the templates of our components using the following API:

let parser: TemplateParser = injector.get(TemplateParser);

parser.parse(templateString, directivesList, pipesList, templateUrl);

The first argument of the parse method of the parser is the template of the component. As second argument we need to pass the list of the directives and pipes visible by the component (this includes the list of directives/pipes declared in the directives/pipes property of ComponentMetadata as well as all other directives/pipes declared in the same way in parent components). In our case we don’t need to pass any value for templateUrl since the template is used inline.

In case CustomHeadingComponent is a top-level component we can parse its template with:

parser.parse('<h1>{{heading}}</h1>', COMMON_DIRECTIVES, COMMON_PIPES, null);

The parse method will return an HtmlAst which can be validated with visitor, similar to the one we use for validation of the TypeScript code.

Definitions of directives and components which need to be resolved

Now lets suppose we have the following components definitions:

// cmp_a.ts

import {Component} from '@angular/core';

import {B} from './cmps_b_c';

@Component({

selector: 'foo',

templateUrl: './a.html',

directives: [B]

})

export class A {}

// cmps_b_c.ts

import {Component} from '@angular/core';

import {D} from './dir_d';

@Component({

selector: 'c',

template: 'c'

})

export class C {}

@Component({

selector: 'b',

template: '<c></c><div d></div>',

directives: [D, C],

inputs: ['foo']

})

export class B {}

// dir_d.ts

import {Directive} from '@angular/core';

@Directive({

selector: '[d]'

})

export class D {}

Lets suppose we want to validate the template of component B:

parser.parse('<c></c><div d></div>', COMMON_DIRECTIVES, COMMON_PIPES, null);

The parser will throw an error similar to:

Template parse errors:

The element 'div' does not have a native attribute 'd'.

This happens because we haven’t included the directive D in the array we pass as second argument to parse.

This means that we need to create a context specific for each of the components in the component tree which includes the visible by the component directives and pipes. In case we want to validate the entire component tree what we need to do is to validate each of the components in their own context. Before doing this, similarly to the AST that the parsers build, we need to create an intermediate representation of the entire component tree.

Lets track the process of building the component tree’s intermediate representation:

- Gather metadata for directive.

- TypeScript generates AST for the directive.

- Based on the AST we create an intermediate Angular specific directive representation.

- We collect the

selector,template,inputs,outputs, etc. - If this directive is not a component return the data collected so far.

- We collect all

directives(note that the directives here are actually references to other classes).- Find the file which contains the definition of the target directive.

- Gather metadata for the directive (notice that this is a recursive call to “Gather metadata for directive” and there could be cyclic dependencies).

- Add the directive with its entire sub tree to the directives array of the component.

- We collect all

pipes(note that the pipes here are actually references to other classes).- Find the file which contains the definition of the target pipe.

- Gather metadata for the pipe.

- Add the pipe to the pipes array of the component.

- We collect the

Alright, now we are done. There are two things to note here:

- There could be cyclic dependencies between components which are typically resolved with

forwardRef. - There are a lot of disk I/O operations because the directives used by any component are most likely located in different files.

We will see what we can do for the I/O operations in the section: “Externalized templates which need to be loaded from disk”, which is generic and could be applied for templates as well as for directives.

Once we’ve gathered useful information for the component tree, lets introduce the algorithm which can be applied for validation:

- Validate given directive.

- If the directive is not a component return.

- Use the parser in order to get the AST of the component’s template (we already have validation for pipes and directives thanks to the parser of Angular. It will throw an error in case it doesn’t find any of the used custom attributes and pipes).

- Validate template’s expressions.

- Validate component’s directives (recursive call).

Validation of Template Expressions

The final thing left here is the procedure for validation of the template’s expressions. Why we haven’t solved this yet?

Lets take a look at the following component:

@Component({

selector: 'custom-cmp',

template: '<h1>{{foo + bar}}</h1>'

})

class CustomComponent {

foo;

bar;

}

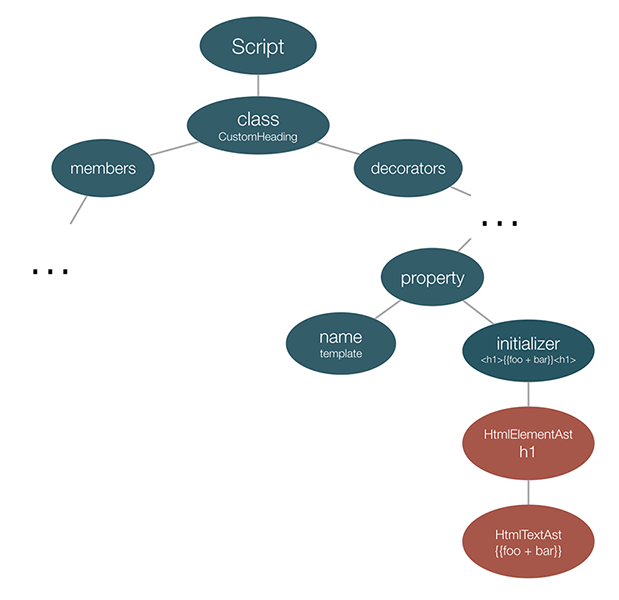

If we parse this source file using TypeScript’s parser and after that we parse its template by using Angular’s TemplateParser we will get:

On the image above we can see two ASTs merged together:

- The TypeScript AST generated by TypeScript’s compiler.

- The Angular template’s AST generated by Angular’s

TemplateParser.

The problem now is that although we’ve parsed both the source file and the template, we haven’t parsed the Angular expression. Angular defines a small DSL which allows us to execute different expressions in the context of given component.

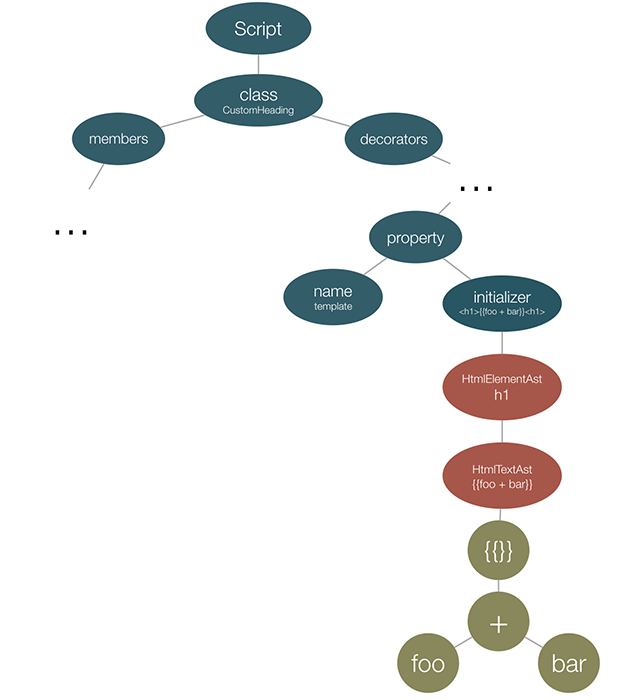

In order to verify that the above expression {{foo + bar}} could be invoked in the context of CustomComponent we need to go through another process of parsing. For this purpose we can use Angular’s parser defined under core/change_detection/parser/parser.ts.

We need to get reference to its instance and parse the expression. After that we’ll get the following mixture of ASTs:

Now, at this point, we can traverse the bottom most AST and see whether the identifiers there exist in the corresponding symbol table (which is the instance of the CustomComponent controller).

Externalized templates which need to be loaded from disk

Now lets suppose instead of template our component uses templateUrl. This means that the validator need to read the template from the disk, in a directory (usually) relative to the component’s definition.

The disk I/O operations are slow:

Latency Comparison Numbers

--------------------------

L1 cache reference 0.5 ns

Branch mispredict 5 ns

L2 cache reference 7 ns 14x L1 cache

Mutex lock/unlock 25 ns

Main memory reference 100 ns 20x L2 cache, 200x L1 cache

Compress 1K bytes with Zippy 3,000 ns 3 us

Send 1K bytes over 1 Gbps network 10,000 ns 10 us

Read 4K randomly from SSD* 150,000 ns 150 us ~1GB/sec SSD

Read 1 MB sequentially from memory 250,000 ns 250 us

Round trip within same datacenter 500,000 ns 500 us

Read 1 MB sequentially from SSD* 1,000,000 ns 1,000 us 1 ms ~1GB/sec SSD, 4X memory

Disk seek 10,000,000 ns 10,000 us 10 ms 20x datacenter roundtrip

Read 1 MB sequentially from disk 20,000,000 ns 20,000 us 20 ms 80x memory, 20X SSD

Send packet CA->Netherlands->CA 150,000,000 ns 150,000 us 150 ms

This means that in the perfect scenario we want to read external templates from the disk only when they change. This could be achieved with something like fs.watch or any of its high-level wrappers. Once a change is discovered, this need to update only the impacted region.

Current Progress

A few weeks ago I developed a few rules for tslint which add some custom Angular 2 specific validation behavior. The project is located in the master branch of the ng2lint repository.

According to npm on average it has 150 downloads per day.

The rules I develop include:

- Directive selector type.

- Directive selector name convention.

- Directive selector name prefix.

- Component selector type.

- Component selector name convention.

- Component selector name prefix.

- Use

@Inputinstead of inputs decorator property. - Use

@Outputinstead of outputs decorator property. - Use

@HostListenersand@HostBindingsinstead of host decorator property. - Do not use the @Attribute decorator (implemented by PreskoIsTheGreatest).

Possible improvement here is extension of the default walkers that we already have with AngularRuleWalker. For instance adding operations such as:

visitDirectiveMetadatavisitComponentMetadatavisitHostListener- etc.

could save us form a lot of boilerplate code in ng2lint.

Another possible extension is validation of the file names we lint based on a semantics gathered from the file’s content.

For instance, if we find out that inside of given file there’s definition of a component we can validate that the file name follows the name convention:

NAME.component.ts

The last weekend I spend playing with more advanced implementation of the linter which aims validation for correctness. The entire progress is located in the advanced branch of ng2lint.

In this branch I implemented the following:

- Building in-memory intermediate representation of the component tree.

- Reads externalized templates from disk.

- Recursively validating components' templates for missing pipes/directives declared for given sub tree.

- Parsing component’s templates.

Tasks pending are:

- Parse the inlined expressions and verify that all the identifiers are defined.

- Integrate both tools together. This will allow the “validating correctness module” to use the error reporting mechanism of

tslintand work out of the box with editors like VSCode, WebStorm, etc. - Handle cyclic references.

Conclusion

The process of building a complete linter for Angular 2 is quite challenging because of several reasons:

- Computational intensity.

- Various intermediate code representations.

- Integration with the existing compiler of TypeScript.

- Integration with existing linters such as

tslintfor working out of the box error reporting mechanism.

Fortunately, neither of the challenging tasks is not related to nondeterminism introduced by the framework. The Angular core team did great design decisions for making the static code analysis and tooling possible.

Resources

- ng2lint’s Official Repository

- tslint’s Official Page

- Angular 2’s Official Repository

- TypeScript’s Official Repository

- Modern Compiler Design 2nd ed. 2012 Edition

- Modern Compiler Implementation in Java 2nd Edition

- Finite Automata

- Regular Expressions

- Context-free grammars

- Extended Backus–Naur Form

- Abstract syntax trees