Ahead-of-Time Compilation in Angular

Edit · Aug 14, 2016 · 17 minutes read · Follow @mgechev

Recently I added Ahead-of-Time (AoT) compilation support to angular-seed and got a lot of questions about the new feature. In order to answer most of them, we will start from the beginning by explaining the following topics:

- Why we need compilation in Angular?

- What needs to be compiled?

- How it gets compiled?

- When the compilation takes place? Just-in-Time (JiT) vs Ahead-of-Time (AoT).

- What we get from AoT?

- How the AoT compilation works?

- Do we loose anything from using AoT vs JiT?

Why we need compilation in Angular?

The short answer of this question is - We need compilation for achieving higher level of efficiency of our Angular applications. By efficiency I mostly mean performance improvements but also energy and sometimes bandwidth consumption.

AngularJS 1.x had quite a dynamic approach for both rendering and change detection. For instance, the AngularJS 1.x compiler is quite generic. It is supposed to work for any template by performing a set of dynamic computations. Although this works great in the general case, the JavaScript Virtual Machines (VM) struggles with optimizing the calculations on lower level because of their dynamic nature. Since the VM doesn’t know the shapes of the objects which provide context for the dirty-checking logic (i.e. the so called scope), it’s inline caches get a lot of misses which slows the execution down.

Angular, version 2 and above, took different approach. Instead of using the same logic for performing rendering and change detection for each individual component, the framework generates VM-friendly code at runtime or build time. This allows the JavaScript virtual machine to perform property access caching and execute the change detection/rendering logic much faster.

For instance, take a look at the following example:

// ...

Scope.prototype.$digest = function () {

'use strict';

var dirty, watcher, current, i;

do {

dirty = false;

for (i = 0; i < this.$$watchers.length; i += 1) {

watcher = this.$$watchers[i];

current = this.$eval(watcher.exp);

if (!Utils.equals(watcher.last, current)) {

watcher.last = Utils.clone(current);

dirty = true;

watcher.fn(current);

}

}

} while (dirty);

for (i = 0; i < this.$$children.length; i += 1) {

this.$$children[i].$digest();

}

};

// ...

This snippet is copied from my lightweight AngularJS 1.x implementation. Above we perform a Depth-First-Search over the entire scope tree, looking for changes in our bindings. This approach will work for any directive. However, it is obviously slower compared to code which is directive specific:

// ...

var currVal_6 = this.context.newName;

if (import4.checkBinding(throwOnChange, this._expr_6, currVal_6)) {

this._NgModel_5_5.model = currVal_6;

if ((changes === null)) {

(changes = {});

}

changes['model'] = new import7.SimpleChange(this._expr_6, currVal_6);

this._expr_6 = currVal_6;

}

this.detectContentChildrenChanges(throwOnChange);

// ...

The snippet above contains a piece of the implementation of the generated detectChangesInternal method of a compiled component from the angular-seed project. It gets the values of the individual bindings by using a direct property access and compares them with the new values using the most efficient way. Once it finds that their values are different, it updates only the impacted DOM elements.

By answering the question “Why we need compilation?” we answered the question “What needs to be compiled?” as well. We want to compile the templates of the components to JavaScript classes. These classes have methods that contain logic for detecting changes in the bindings and rendering the user interface. This way we are not coupled to the underlying platform (except the markup format). In other words, by having a different implementation of the renderer we can use the same AoT compiled component and render it without any changes in the code. So the component above could be rendered in NativeScript, for instance, as soon as the renderer understands the passed arguments.

Just-in-Time (JiT) vs Ahead-of-Time (AoT)

This section contains answer of the question:

- When the compilation takes place?.

The cool thing about the Angular’s compiler is that it can be invoked either runtime (i.e. in the user’s browser) or build-time (as part of the build process). This is due to the portability property of Angular - we can run the framework on any platform with JavaScript VM so why to not make the Angular compiler run both in browser and node?

Flow of events with Just-in-Time Compilation

Lets trace the typical development flow without AoT:

- Development of Angular application with TypeScript.

- Compilation of the application with

tsc. - Bundling.

- Minification.

- Deployment.

Once we’ve deployed the app and the user opens her browser, she will go through the following steps (without strict CSP):

- Download all the JavaScript assets.

- Angular bootstraps.

- Angular goes through the JiT compilation process, i.e. generation of JavaScript for each component in our application.

- The application gets rendered.

Flow of events with Ahead-of-Time Compilation

In contrast, with AoT we get through the following steps:

- Development of Angular application with TypeScript.

- Compilation of the application with

ngc.- Performs compilation of the templates with the Angular compiler and generates (usually) TypeScript.

- Compilation of the TypeScript code to JavaScript.

- Bundling.

- Minification.

- Deployment.

Although the above process seems lightly more complicated the user goes only through the steps:

- Download all the assets.

- Angular bootstraps.

- The application gets rendered.

As you can see the third step is missing which means faster/better UX and on top of that tools like angular-seed and angular-cli will automate the build process dramatically.

In recap we can say that the main differences between JiT and AoT in Angular are:

- The time when the compilation takes place.

- JiT generates JavaScript (TypeScript doesn’t make a lot of sense since the code needs to be compiled to JavaScript in the browser), however, AoT usually generates TypeScript.

A minimalistic AoT compilation demo you can find in my GitHub account.

Ahead-of-Time Compilation in Depth

This section answers the questions:

- What artifacts the AoT compiler produces?

- What the context of the produced artifacts is?

- How to develop both: AoT friendly and well encapsulated code?

We will go quickly through the compilation because there’s no point to explaining the entire @angular/compiler line-by-line. If you’re interested in the process of lexing, parsing and code generation, you can take a look at the talk “The Angular 2 Compiler” by Tobias Bosch or this slide deck.

The Angular template compiler receives as an input a component and a context (we can think of the context as a position in the component tree) and produces the following files:

*.ngfactory.ts- we’ll take a look at this file in the next section.*.css.shim.ts- scoped CSS file based on theViewEncapsulationmode of the component.*.metadata.json- metadata associated with the current component (orNgModule). We can think of it as a JSON representation of the objects we pass to the@Component,@NgModuledecorators.

* is a placeholder for the file’s name. For hero.component.ts, the compiler will produce: hero.component.ngfactory.ts, hero.component.css.shim.ts, and hero.component.metadata.json.

*.css.shim.ts is not very interesting for the purpose of our discussion so we won’t describe it in details. If you what to know more about *.metadata.json you can take a look at the section: “AoT and third-party modules”.

Inside *.ngfactory.ts.

The file *.ngfactory.ts contains the following definitions:

_View_{COMPONENT}_Host{COUNTER}- we call this an “internal host component”._View_{COMPONENT}{COUNTER}- we call this an “internal component”.

…and two functions:

viewFactory_{COMPONENT}_Host{COUNTER}viewFactory_{COMPONENT}{COUNTER}

Above {COMPONENT} is the name of the component’s controller and {COUNTER} is an unsigned integer.

Both classes extend AppView and implement the following methods:

createInternal- renders the component.destroyInternal- performs clean-up (removes event listeners, etc.).detectChangesInternal- detects changes with method implementation optimized for inline caching.

The factory functions above are only responsible for instantiation of the generated AppViews.

As I mentioned above, the detectChangesInternal contains VM friendly code. Let’s take a look at the compiled version of the template:

<div>{{newName}}</div>

<input type="text" [(ngModel)]="newName">

The detectChangesInternal method going to look something like:

// ...

var currVal_6 = this.context.newName;

if (import4.checkBinding(throwOnChange, this._expr_6, currVal_6)) {

this._NgModel_5_5.model = currVal_6;

if ((changes === null)) {

(changes = {});

}

changes['model'] = new import7.SimpleChange(this._expr_6, currVal_6);

this._expr_6 = currVal_6;

}

this.detectContentChildrenChanges(throwOnChange);

// ...

Let’s suppose that currVal_6 has value 3 and this_expr_6 has value 1, and now lets trace the method’s execution:

For call like: import4.checkBinding(1, 3), in production mode, checkBinding perform the following check:

1 === 3 || typeof 1 === 'number' && typeof 3 === 'number' && isNaN(1) && isNaN(3);

The expression above will return false, so we’re going to store the change and update the model value of the NgModel directive instance. Right after that the detectContentChildrenChanges will be invoked which will invoke the detectChangesInternal method for all the content children. Once the NgModel directive finds out about the changed value of the model property, it’ll update the corresponding element by (almost) directly calling the renderer.

Nothing unusual and terribly complicated so far.

The context property

Maybe you’ve noticed that within the internal component we’re accessing the property this.context. The context of the internal component is the instasnce of the component’s controller itself. So for instance:

@Component({

selector: 'hero-app',

template: '<h1>{{ hero.name }}</h1>'

})

class HeroComponent {

hero: Hero;

}

…this.context will equal to new HeroComponent(). This means that in detectChangesInternal we have to access this.context.name. Here comes a problem. If we want to emit TypeScript as output of the AoT compilation process we must make sure we access only public fields in the templates of our components. Why is that? As we already mentioned the compiler can generate both TypeScript and JavaScript. Since TypeScript has access modifiers, and enforces access only to public properties outside the inheritance chain, inside the internal component we cannot access any private properties part of the context object, so both:

@Component({

selector: 'hero-app',

template: '<h1>{{ hero.name }}</h1>'

})

class HeroComponent {

private hero: Hero;

}

…and…

class Hero {

private name: string;

}

@Component({

selector: 'hero-app',

template: '<h1>{{ hero.name }}</h1>'

})

class HeroComponent {

hero: Hero;

}

will throw a compile time error in the generated *.ngfactory.ts. In the first example the internal component cannot access hero since it’s private within HeroComponent, and in the second case the internal component won’t be able to access hero.name, since name is private inside Hero.

AoT and encapsulation

Alright, we’ll bind only to public properties and invoke only public methods inside of the templates but what happens with the component encapsulation? This may doesn’t seem like a big problem at first, but imagine the following scenario:

// component.ts

@Component({

selector: 'third-party',

template: `

{{ _initials }}

`

})

class ThirdPartyComponent {

private _initials: string;

private _name: string;

@Input()

set name(name: string) {

if (name) {

this._initials = name.split(' ').map(n => n[0]).join('. ') + '.';

this._name = name;

}

}

}

The component above has a single input - name. Inside of the name setter it calculates the value of the _initials property. We can use the component as follows:

@Component({

template: '<third-party [name]="name"></third-party>'

// ...

})

// ...

Since in JiT mode, the Angular compiler generates JavaScript, this works perfect! Each time the value of the name expression changes and equals to truthy value, the _initials property will be recomputed. However, the implementation of ThirdPartyComponent is not AoT-friendly (to make sure you access only public/existing fields in your templates you can use codelyzer. If we want to do so we have to change it to:

// component.ts

@Component({

selector: 'third-party',

template: `

{{ initials }}

`

})

class ThirdPartyComponent {

initials: string;

private _name: string;

@Input()

set name(name: string) {...}

}

And thus something like this will be possible:

import {ThirdPartyComponent} from 'third-party-lib';

@Component({

template: '<third-party [name]="name"></third-party>'

// ...

})

class Consumer {

@ViewChild(ThirdPartyComponent) cmp: ThirdPartyComponent;

name = 'Foo Bar';

ngAfterViewInit() {

this.cmp.initials = 'M. D.';

}

}

…which will leave the ThirdPartyComponent component in an inconsistent state. The value of the _name property of the ThirdPartyComponent’s instance will be Foo Bar but the value of initials will be M. D. (instead of F. B.).

The answer of how to solve this issue is rooted in the Angular’s code. In case we want to make our code AoT-friendly (i.e. bind only to public properties and methods in our templates), and in the same time keep encapsulation, we can use the TypeScript annotation /** @internal */:

// component.ts

@Component({

selector: 'third-party',

template: `

{{ initials }}

`

})

class ThirdPartyComponent {

/** @internal */

initials: string;

private _name: string;

@Input()

set name(name: string) {...}

}

The initials property will be public but if we compile our third-party library with tsc and the --stripInternal and --declarations flags set, the initials property will be omitted from the type declarations file (e.g. d.ts file) for ThirdPartyComponent. This way we will be able to access it within the bounderies of our library but it won’t be accessible by its consumers.

Recap of ngfactory.ts

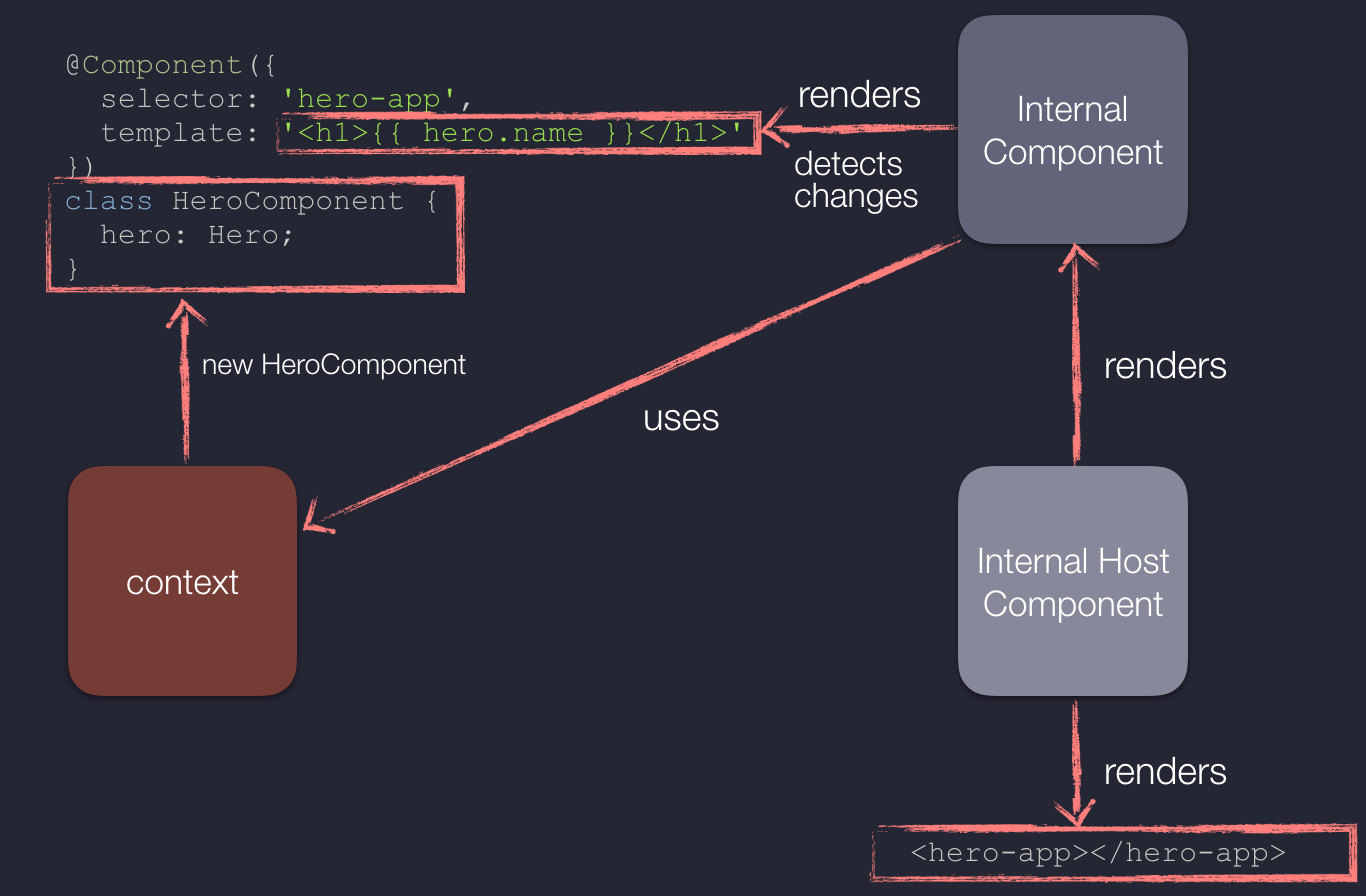

Now lets make a quick recap of what’s going on behind the scene! Lets suppose we have the HeroComponent from the example above. For this component, the Angular compiler will generate two classes:

_View_HeroComponent_Host1- the internal host component._View_HeroComponent1- the internal component.

_View_HeroComponent1 will be responsible for rendering the template of HeroComponent and also, performing change detection. When performing change detection _View_HeroComponent1 will compare the current value of this.context.hero.name with the previous stored value. In case the values are different, the <h1/> element will be updated. This means that we need to make sure that this.context.hero and hero.name are both public. This can be verified by using codelyzer.

On the other hand, _View_HeroComponent_Host1 will be responsible for rendering <hero-app></hero-app> (the host element), and _View_HeroComponent1 itself.

You can find the entire example summarized on the diagram below:

AoT vs JiT - development experience

In this section we’ll discuss another point of difference between the development experience in using AoT vs JiT.

Maybe the biggest difference between JiT that impacts the development experience is the fact that in JiT mode the internal component and the internal host component will be defined in JavaScript. This means that the fields in our components’ controllers are always going to be public so we can’t get any compile-time errors because our internal component accesses any private fields of its context.

In JiT once we bootstrap the application we already have our root injector and all the directives available in the root component (they are included in BrowserModule and all other modules that we import in the root module). This metadata will be passed to the compiler for the process of compilation of the template of the root component. Once the compiler generates the code with JiT, it has all the metadata which should be used for the generation of the code for all child components. It can generate the code for all of them since it already knows not only which providers are available at this level of the component tree but also which directives are visible there.

This will allow the compiler know what to do when it visit an element in the template. For instance, the element <bar-baz></bar-baz> can be interpreted in two different ways depending on whether there’s a directive/component with selector bar-baz available or not. Whether the compiler will only create an element bar-baz or also instantiate the component associated with the selector bar-baz depends on the metadata at the current phase of the compilation process (on the current state).

Here comes the problem. How at build time we would know what directives are accessible on all levels of the component tree? Thanks to the great design of Angular we can perform a static-code analysis and find this out! Chuck Jazdzewski and Alex Eagle did amazing job in this direction by developing the MetadataCollector and other related modules. What the collector does is to walk the component tree and extract the metadata for each individual component and NgModule. This involves some awesome techniques which unfortunately are out of the scope of this blog post.

AoT and third-party modules

Alright, so the compiler needs metadata for the components in order to compile their templates. Lets suppose that in our application we use a thrid-party component library. How does the Angular AoT compiler knows the metadata of the components defined there if they are distributed as plain JavaScript? It oesn’t. In order to be able to compile ahead-of-time an application, referencing an external Angular library, the library needs to be distributed with the *.metadata.json produced by the compiler.

For further reading on how to use the Angular compiler, you can take a look at the following link. For an example of how you can build your custom library in order to be AoT-ready, you can peek at the angular/mobile-toolkit.

What we get from AoT?

As you might have already guessed, from AoT we get performance. The initial rendering performance of each Angular applications we develop with AoT will be much faster compared to a JiT one since the JavaScript Virtual Machine needs to perform much less computations. We compile the templates to JavaScript only once as part of our development process, after that the user gets compiled templates for free!

On the image below you can see how much time it takes to perform the initial rendering with JiT:

On the image below you can see how much time it takes to perform the initial rendering with AoT:

Another awesome thing about the Angular compiler is that it can emit not only JavaScript but TypeScript as well. This allows us to perform type checking in templates!

Since the templates of the application are pure JavaScript/TypeScript, we know exactly what and where is used. This allows us to perform effective tree-shaking and drop all the directives/modules which are not used by the application out of the production bundle! On top of that we don’t need to include the @angular/compiler module in the application bundle since we don’t need to perform compilation at runtime!

Note that for large to medium size applications the bundle produced after performing AoT compilation will most likely be bigger compared to same application using JiT compilation. This is because the VM friendly JavaScript produced by ngc is more verbose compared to the HTML-like templates, and also includes dirty-checking logic. In case you want to drop the size of the app you can perform lazy loading which is supported natively by the Angular router!

In some cases, JiT compilation cannot be performed at all. Since JiT both generates and evaluates code in the browser it uses eval. CSP and some specific environments will not allow us to dynamically evaluate the generated source code.

Last but not least, energy efficiency! The user devices need to perform even less since it receives already compiled code. This reduces battery consumption but how much? Here are the results of a some funny calculations I did :-):

Based on findings by the research “Who Killed My Battery: Analyzing Mobile Browser Energy Consumption” (by N. Thiagarajan, G. Aggarwal, A. Nicoara, D. Boneh, and J. Singh), the process of downloading and parsing jQuery when visiting Wikipedia takes about 4 Joules of energy. Since the paper doesn’t mention specific version of jQuery, based on the date when it was published I assume it’s talking about v1.8.x. Since Wikipedia uses gzip for compressing their static content this means that the bundle size of jQuery 1.8.3 will be 33K. The gzipped + minified version of @angular/compiler is 103K. This means that it’ll cost us about 12.5J to download the compiler, process it with JavaScript Virtual Machine, etc. (we’re ignoring the fact that we are not performing JiT, which will additionally reduce the processor usage. We do this because in both cases - jQuery and @angular/compiler we’re opening only a single TCP connection, which is the biggest consumer of energy).

iPhone 6s has a battery which is 6.9Wh which is 24840J. Based on the monthly visits of the official page of AngularJS 1.x there will be at least 1m developers who have built on average 5 Angular applications. Each application have ~100 users per day. 5 apps * 1m * 100 users = 500m. In case we perform JiT and we download the @angular/compiler it’ll cost to the Earth 500m * 12.5J = 6250000000J, which is 1736.111111111KWh. According to Google, 1KWh = ~12 cents in the USA, which means that we’ll spend about $210 for recovering the consumed energy for a day. Notice that we even didn’t take the further optimization that we’ll get by applying tree-shaking, which may allow us to drop the size of our application at least twice! :-)

Conclusion

The Angular’s compiler improves the performance of our applications dramatically by taking advantage of the inline caching mechanism of the JavaScript Virtual Machines. On top of that we can perform it as part of our build process which solves problems such as forbidden eval, allows us to perform more efficient tree-shaking, improves the initial rendering time.

Do we loose anything by not performing the compilation at runtime? In some very limited cases we may need to generate the templates of the components on demand. This will require us to load non-compiled components and perform the compilation process in the browser, in such cases we’d need to include the @angular/compiler module as part of our application bundle. Another potential drawback of AoT compiled large to medium applications is the increase in their bundle size. Since the produced JavaScript for the components’ templates has bigger size compared to the templates themselves, this will most likely lead to bigger final bundle.

In general, the AoT compilation is a good technique which is already integrated as part of the angular-seed and angular-cli, so you can take advantage of it today!