Flux in Depth. Overview and Components.

Edit · May 15, 2015 · 16 minutes read · Follow @mgechev

This is the first blog post of the series “Flux in Depth”. Is this “yet the another flux tutorial”? What I have seen so far, while researching flux, were mostly “how-to” tutorials (usually with todo applications), which describe the main components of given flux application and the data flow between them. This is definitely useful for getting a high-level overview of how everything works but in reality there are plenty of other things, which should be taken under consideration. In this series of posts I will try to wire theory with practice and state my own solutions of problem I face on daily basis. Since these solutions might not be perfect, I’d really appreciate giving your opinion in the comments section below.

Introduction

Flux is micro-architecture for software application development, which has unidirectional data flow. It sounds quite abstract but thats what it is. It is technology agnostic, which means that it doesn’t depend on ReactJS, although it was initially introduced by facebook. It is not coupled to a specific place in the stack where it should be used - you can build isomorphic JavaScript applications with flux, like Reza Akhavan pointed out during one JavaScript breakfast. Flux is not even coupled to JavaScript. It just solves a few problems, which are common for MVC.

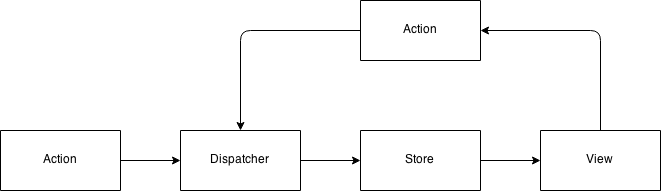

Lets take a look at a diagram, which illustrates the data flow in a flux application:

Flux High-Level Overview

Lets describe what the boxes and the arrows above mean and later we will dig into the data flow. If you’re already familiar with flux, feel free to skip this section.

View

The view is simply composition of components. They might be stateless or stateful. We will talk more about components in the next sections. How exactly we need to compose them and on what level of granularity they should be depends completely on the UI of our application. We have higher level components, which abstract lower level components by composing them. The data is passed from the root component to all its child components, which recursively pass the data used by their children and so on.

Store

The store is not only the model of our application. The store simply contains the state of the UI. When we use stateful components parts of the state could be stored in them but we need to be careful with that.

What state could be kept in the store? We can think of two types of store:

- Model - domain specific data. For example, the todo items in our todo application.

- UI state - the state of our view, which is not relevant to the model. For example, which dialog is opened right now.

One common thing between MVC and flux is that the store should not be aware of its representation and it is better to be unaware of the way our application communicates with the back-end services, although in flux the store and the view are more coupled (because of the UI state)! However, the store in flux is not equals to the model in MVC. Making the UI state external for the components help us create “pure components” (see below) and force the separation of concerns even further. Why this is so awesome? Well, our store is nothing more than a JavaScript object, which could be easily persisted! Imagine the world where you can make a “snapshot” of your UI and save it somewhere (database, localStorage, wherever). Later you can restore this “snapshot” quite easily! If we go on more philosophical level, we can distinguish the state and the model even further. We can have separate component, which represents our domain data and keep only the UI state in the store (which will be some kind of mix between the data stored in our model and the state of our components, like coordinates on the screen, flags whether the components are enabled or disabled, etc.).

This separation will keep the structure of our model completely independent from the view but will bring more complexity because of the additional component.

The store knows only of the existence of:

Dispatcher

A few years ago, Nicholas Zakas published his large scale application architecture. In the core of the architecture there is a sandbox, which implements the publish/subscribe pattern. Publish/subscribe is nothing more than the observer pattern but since in JavaScript we have first-class functions, we can use them instead of observers. We can think of the publish/subscribe object as an event bus (which could be considered more or less as mediator). The main difference between observer and publish/subscribe is that in the latest, it is not responsibility of the subject to keep list of observers, unlike in the classical observer pattern.

Okay, so I said this only in order to tell you that the Dispatcher is simply an event bus. It is a singleton, which owns a map of key-value pairs. The keys in this map are event (action) names and the values are lists of callbacks. The dispatcher has a method called dispatch, which once called with an event name, iterates over all callbacks associated with it and invokes them. Thats it. The implementations may slightly vary but that is the general idea. You can take a look at sample implementation here. In my projects I usually use this implementation as base class for my custom Dispatcher. So far I haven’t needed anything it doesn’t provide.

Action

Actions are even simpler than the Dispatcher. What they do is to define methods, which will be called by the View. These methods accept arguments, which contain further instructions on how the View wants to change the Store. All these methods do is to delegate their calls to the Dispatcher’s dispatch method. This might seems like unnecessary level of indirection. Why would we need to call action from the View, which action immediately delegates its call to the Dispatcher’s dispatch method? Why not simply call the dispatch method from the view? The view only invokes methods of actions, which should be named semantically correctly. The action is responsible for translating these calls to a events, which are understandable by the Store. In this case the actions may combine a few calls at one event or fork given action to two or more different events.

So from the diagram above we can notice that the arrows are in only a single direction. This is one of the “selling points” of flux:

Unidirectional Data Flow

Building MVW applications help us to better structure our client-side code, make it more coherent and less coupled. We can easily isolate our business logic from the view, making our models independent from their representation. This decoupling is achieved using the observer pattern, which is quite handy; it helps us dispatch events in both directions - view to model and vice versa.

However, in complex single-page applications dispatching events in both directions may lead to cascading events, which introduces a tangled weave of data flow and unpredictable results. Flux helps us deal with the issues of MVW and allows us to build highly scalable single-page applications.

It is much easier to follow the unidirectional data flow since we know exactly where the data comes from and to which components it needs to be redirected next. This definitely makes our applications easier for understanding but there is one more feature, which help us deal with complexity:

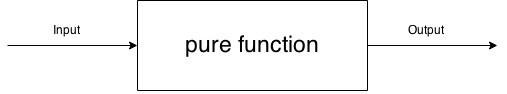

Stateless Components

In flux the user interface is a composition of stateless UI components (they may keep some component-specific state but we will talk about this in a bit). The components do not depend on any external mutable state. The user interface they render is entirely determined by the received input by their parent component. May be it seems like a brand new, innovative idea, however it is a well known concept, which comes from the world of functional programming.

It is much easier to think of the functions as black boxes, which accept input and return output:

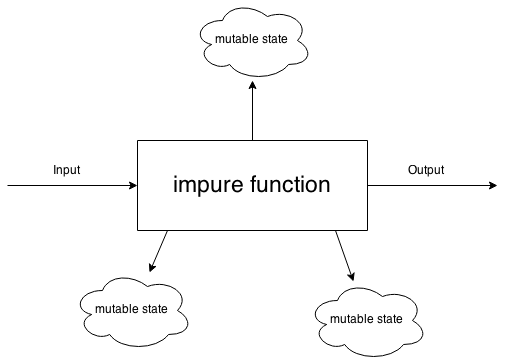

Rather than as something, which does its job by depending on external mutable resources:

According to Wikipedia a pure function is:

In computer programming, a function may be described as a pure function if both these statements about the function hold:

- The function always evaluates the same result value given the same argument value(s). The function result value cannot depend on any hidden information or state that may change as program execution proceeds or between different executions of the program, nor can it depend on any external input from I/O devices (usually—see below).

- Evaluation of the result does not cause any semantically observable side effect or output, such as mutation of mutable objects or output to I/O devices (usually—see below).

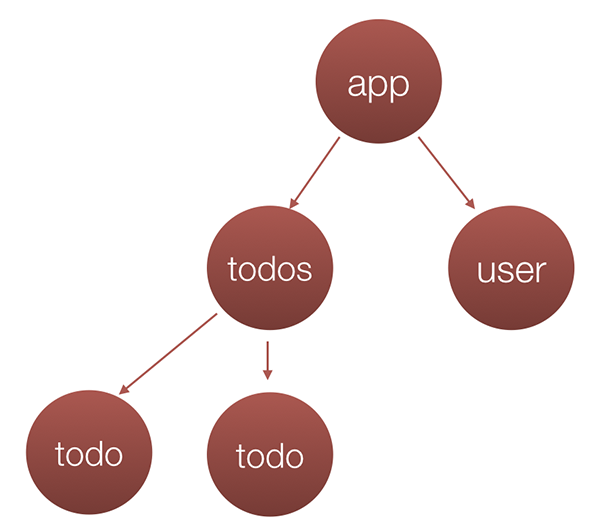

How we can make our components pure? Definitely they should not use any global variables because their result (rendered UI), should not depend on anything else except the properties they accept. But that’s not all. If the data passed to the component tree is mutable given component may change the data used by another component. For example, we can have the following component tree:

And the following data applied to it:

{

photoUrl: "photo.png",

firstName: "Foo",

lastName: "Bar",

age: 42,

updated: 1429260707251,

todos: [{

title: "Save the Universe",

updated: 1429260907251,

completed: true

}, {

title: "Write tests",

updated: 1429260917251,

completed: false

}]

}

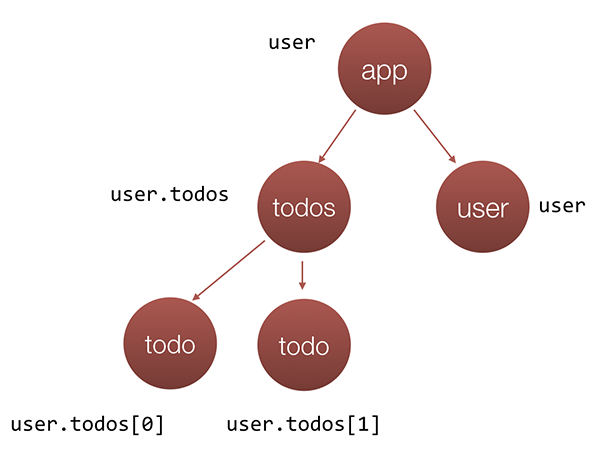

If we call the object above user, in a flux-like architecture the data will be distributed across the components in the following way:

If the User component needs to display the number of pending todo items, we may have the following snippet in its implementation:

user.todos = user.todos.filter(u => !u.completed);

It definitely looks elegant, we’re applying the high-order function filter over the user’s todo items. However, this way we’re creating an impure component since it produces side-effect, i.e. changes data, which is used by another component. The change in user.todos will introduce an issue - the Todos component will render only the not completed todo items. Sometimes, such side effects could be very unpleasant and complex for debugging.

Immutable Data

How we can deal with such side effects? We can use something called immutable data, which according to Wikipedia is defined as:

In object-oriented and functional programming, an immutable object is an object whose state cannot be modified after it is created.

You can check out my talk on using immutable data in Angular here.

In order to introduce the immutability in our application we have three options:

- Use wrappers around the standard JavaScript primitives, which makes the data immutable (for example with library like Immutable.js)

- Use ES5

Object.freeze - Combination between both approaches

Lets create an immutable list using Immutable.js:

let list = new Immutable.List([1, 2]);

let foo = {};

let newList = list.push(foo);

console.log(list.toString()); // List [ 1, 2 ]

console.log(newList.toString()); // List [ 1, 2, [object Object] ]

newList.get(2).baz = 42;

console.log(foo.baz); // 42

In the snippet above we can notice that:

- Each operation, which will eventually mutate the data structure returns a new immutable object (list in this case), so

list !== newList - The returned immutable object from the mutation operation is the same as the initial list but with the modification applied

- The list can contains heterogeneous data (numbers and objects)

- The list items are not immutable, we pushed the

fooobject inside the list and changed it right after that

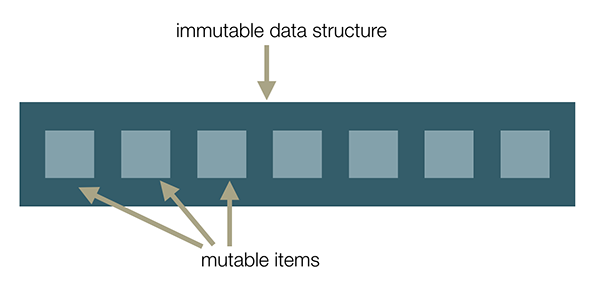

It is not responsibility of Immutable.js to make the entries immutable. We can think of Immutable.js’ list as a thin wrapper around the standard JavaScript array:

We can simply access any of the mutable items inside the immutable data structure…:

…and change it:

Which is not cool. In order to fix this behavior we can use Object.freeze.

If we use Object.freeze:

let foo = { bar: {} }

Object.freeze(foo);

foo.baz = 'foobar';

console.log(foo.baz); // undefined

foo.bar.baz = 'foobar';

console.log(foo.bar.baz); // 'foobar'

Which means that Object.freeze doesn’t do deep freeze of the objects.

What we can do is to:

- Use Immutable.js for our data structures

- Deep freeze our data items

Is it necessary to use immutable data? No. It may eventually lead to some performance slowdowns (or not) but it will make your debugging experience even easier since your components won’t produce any side effects, in case you’ve already stopped touching the global things! If you’re using immutable data you will also make sure you’ve put some boundaries in your project. If new team members join they will be forced to use immutable data structures and you won’t find someone trying to take cross cuts by changing the mutable state.

Stateful vs Stateless

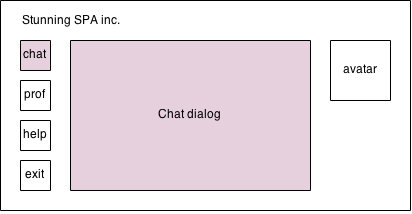

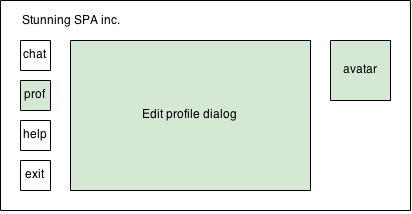

It is recommended your flux components to be stateless, completely stateless! For example take look at the following mocks:

This is front page of “Stunning SPA inc.”…The user has four buttons in the left-hand side of the screen:

- Chat

- Profile

- Help

- Exit

Once the chat button is pressed all opened dialogs should be closed and the chat dialog should be opened in the middle area of the page. Once the profile button is pressed all opened dialogs should be closed and the “Edit profile dialog” should be opened. Pretty straight forward scenario.

Lets implement the Dialog component in ReactJS:

class Dialog extends React.Component {

constructor() {

this.state = {};

this.state.hidden = true;

}

open() {

this.setState({

hidden: false

});

}

close() {

this.setState({

hidden: true

});

}

render() {

let classNames = 'dialog';

if (this.state.hidden) {

classNames += ' hidden';

}

return (

<div className={classNames}>

<header>{{this.props.title}}</header>

<content>{{this.props.content}}</content>

</div>

);

}

}

…and we can use it like:

class App extends React.Component {

openDialog(dialog) {

for (let d in dialogs) {

this.refs[d].close();

}

this.refs[dialog].open();

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<div className="left-sidebar">

<button onClick={this.openDialog.bind(this, 'chat')}>Chat</button>

<button onClick={this.openDialog.bind(this, 'profile')}>Profile</button>

</div>

<div className="main-area">

<Dialog ref="chat" title="Chat" content={some_content}></Dialog>

<Dialog ref="profile" title="Chat" content={some_content}></Dialog>

</div>

<div className="right-sidebar">

<Avatar profile={this.user}></Avatar>

</div>

</div>

);

}

}

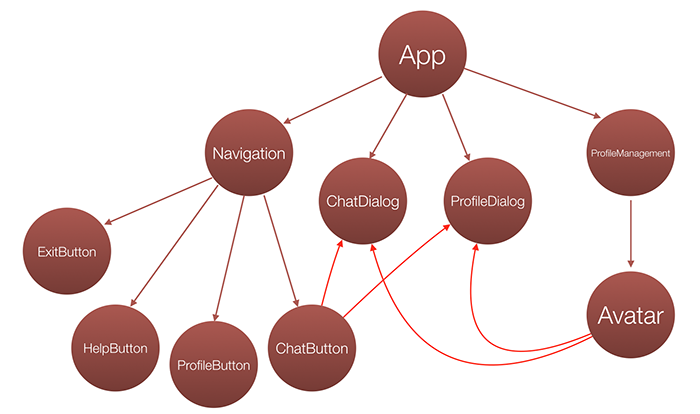

This looks pretty reasonable. But what if we add more components to the page sections? We may have much more complex navigation with different effects, different components and further logic. Our right section may become more complex as well by adding more components for controlling the user’s profile, etc. In such case we should take advantage of the components’ composability and decompose our App into a few simple components. So our App component will look something like this:

class App extends React.Component {

render() {

return (

<div>

<Navigation></Navigation>

<div className="main-area">

<Dialog ref="chat" title="Chat" content={some_content}></Dialog>

<Dialog ref="profile" title="Chat" content={some_content}></Dialog>

</div>

<ProfileManagement></ProfileManagement>

</div>

);

}

}

Okay…but how will the Navigation component tell the App component when to open any of the dialogs? Remember our ProfileManagement component needs to be able to open the profile dialog as well…? We can workaround this issue by passing callbacks:

class App extends React.Component {

openDialog(dialog) {

for (let d in dialogs) {

this.refs[d].close();

}

this.refs[dialg].open();

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<Navigation openDialog={this.openDialog.bind(this)}></Navigation>

<div className="main-area">

<Dialog ref="dialog" title="Chat" content={some_content}></Dialog>

<Dialog ref="dialog" title="Chat" content={some_content}></Dialog>

</div>

<ProfileManagement openDialog={this.openDialog.bind(this)}></ProfileManagement>

</div>

);

}

}

Now inside the Navigation and ProfileManagement components we can invoke:

this.props.openDialog('chat'); // open the chat dialog

this.props.openDialog('profile'); // open the edit profile dialog

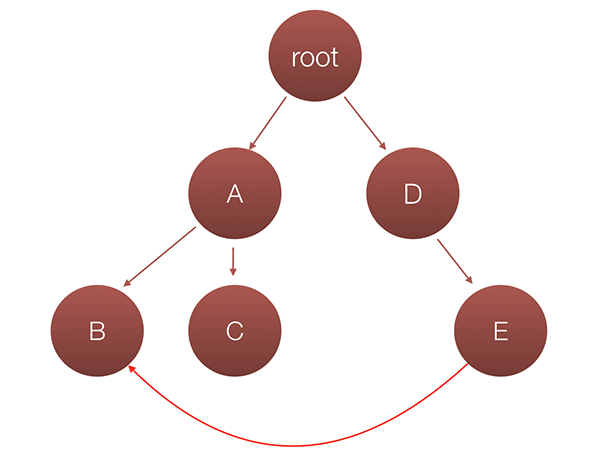

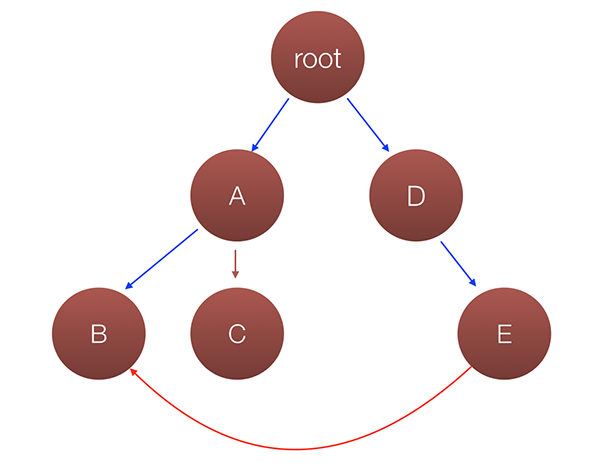

It started getting kind of messy, didn’t it? It is still manageable but imagine we have a deep tree with nested components and one component needs to be able to change the state of another component from entirely different subtree. For example in the picture bellow, component E needs to change the state of component B:

This is not much different from our “Stunning SPA inc” app, where the ProfileManagement component needs to be able to change the state of the dialog components:

We solved the issue there by passing callbacks, so in our example application it will look something like this:

Since we have data flow only from parent components to successors, we need to pass two callbacks here:

- One to component

B - One to component

E

Once component E needs to change the state of component B, it will invoke the callback passed to it, which will invoke the callback passed to B, which will somehow change the component state. Yeah, it is confusing. It gets even messier if we need to have more components communicating between each other and their common ancestor is the root node. Imagine what an explosion of callbacks and tangled logic will be…

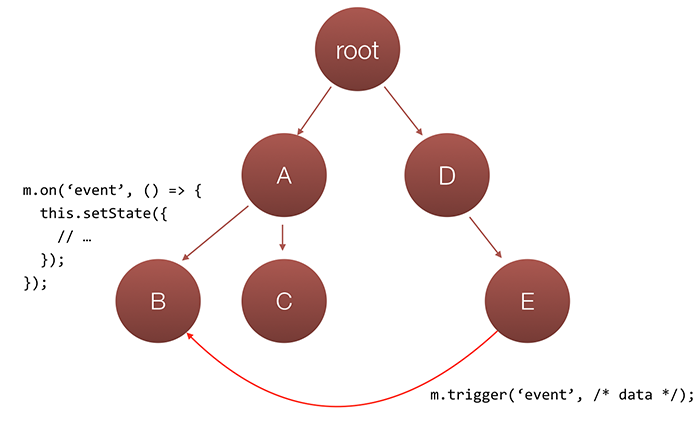

What else can we do? Can’t we make E and B communicating directly? Yeah…I guess…:

We can use custom event system. Implementing the publish/subscribe pattern and allowing global access to our pubsub object will fix this issue. This is actually the recommendation by facebook. But do you see something wrong here? This violates everything we believe in…we just buried all the positives we got from flux so far…

- Pure components

- Unidirectional data flow

All our components are going to have access to a global mutable object and through this object they are going to achieve bidirectional data flow…plenty of dirty words in a single sentence! Did you see how only a second of inattention may cause you regrets during your entire life…! I believe this recommendation by facebook was published before flux was released, otherwise they hate us and want us to suffer!

Solution

We can handle this issue by using the “flux way”. We can externalize the state of all our components and put it into the store. This means that our dialog should receive as input whether it should be open or not:

class Dialog extends React.Component {

render() {

let classNames = 'dialog';

if (this.props.hidden) {

classNames += ' hidden';

}

return (

<div className={classNames}>

<header>{{this.props.title}}</header>

<content>{{this.props.content}}</content>

</div>

);

}

}

It should not have its own opinion on the topic! Okay, so how we should proceed if we want to open the chat dialog? I will explain it with the disclaimer that it might sound like a huge overhead but I promise that it’s worth trying it! In the following use case in a casual format you can read the exact steps the user and the app need to perform:

- The user clicks the “Chat” button

- The button

onClickhandler is being invoked - The handler delegate its call to an Action (for example

UIActions.openChat) UIActions.openChatdelegates its call to theDispatcherby providing further information about the type of the event (whether it is server or an UI event) and the event name- The

Storehandles the event thrown by theDispatcherand changes the flagsUIState.chatDialogOpentotrueandUIState.profileDialogOpentofalse - The

Storethrows new change event - The

Appcomponent catches the change event and propagates theStoredown through the tree

This is how we took advantage of all our flux components! Yeah, it sounds complex, I believe, but you’ll get used to it and you’ll love it! All new ideas are hard to grasp initially but once you find value in them you just can’t live without them!

…but what about stateful components…

We said that we may also have stateful components in some rare cases…Here is an example - your dialogs are draggable, you can keep the component’s coordinates in their state. People can argue with me about this and they will have their point. For example react-dnd externalizes the component’s coordinates in the Store as well. However, in most cases I think we can violate the rule about stateless components and just keep the component specific state inside itself. However, if another component needs to change state of given component we should definitely externalize it and apply flux (just like in the scenario above).

But how we can keep such state persistent if we need to? A few weeks ago I wrote a mixin called react-pstate, which allows you to persist your component’s state. You can take a look at the module here.

For now we can stop our flux journey here and keep talking about store and communication with external services in the next post of the series.