Faster Angular Applications - Part 2. Pure Pipes, Pure Functions and Memoization

Edit · Nov 12, 2017 · 11 minutes read · Follow @mgechev

In this post, we’ll focus on techniques from functional programming we can apply to improve the performance of our applications, more specifically pure pipes, memoization, and referential transparency. If you haven’t read the first part of the “Faster Angular Applications” series, I’d recommend you to take a look at it or at least get familiar with the structure of the business application that we’re optimizing.

The code for this blog post is available at my GitHub account:

Goals for Optimization

In this section, we’ll see how we can reduce the number of computations going on in the application even further! The three specific features that we’re going to focus on are:

- Adding an employee to a department.

- Removing an employee from a department.

- Initial rendering performance.

Optimizing the Mutation Operations

There’s something in common between the first two points above - they mutate the list of employees for a specific department. Since in the previous blog post we switched to OnPush change detection strategy with Immutable.js, now if we add or remove an employee from any of the lists we’ll get a new immutable list. This will trigger the change detection for the EmployeeListComponent and its child components - ListComponent and NameListComponent which will require re-evaluation of all the expressions in the templates of these components.

Let’s see how this looks in practice. For the purpose, we can add a log statement in the ListComponent’s calculate method to see when it gets invoked. Here’s the final result:

From the GIF above we can see that while typing the change detection doesn’t get invoked - cool! We did this optimization in the previous post from the series.

We can also notice that when the user adds a new employee the calculate method gets invoked 71 times. Given that we initially have 70 employees on the sales list, this means that on top of calculating the numeric value for the new employee we also recalculate it for all the already existing employees. This way we perform 70 useless calculations which in case of a computationally intensive business calculation can have some serious performance implications!

What we’d want to happen is:

- During the initial application rendering, we calculate the numeric values for all the employees and visualize them.

- When we add a new entry, we calculate the numeric value only for the newly added employee, without performing any redundant calculations for the already existing employees, since we have their numeric values from the rendering phase.

To implement this behavior, let’s take a look at our mocked business calculation - the function of Fibonacci:

const fibonacci = (num: number): number => {

if (num === 1 || num === 2) {

return 1;

}

return fibonacci(num - 1) + fibonacci(num - 2);

};

It has two fundamental properties which are typical for all mathematical functions:

- It does not perform any side effects - when calculating the employee’s numeric value, we don’t send any network requests, touch local storage, log anything in the console, etc.

- It returns the exact same result for the same set of arguments -

fibonacci(1)is always 1, same forfibonacci(n)which always is going to return the samekwheren ∈ ℕ, k ∈ ℕ.

Such functions in the world of functional programming are called pure functions. All mathematical functions are pure, and for performing a meaningful business calculation for the employees’ numeric value, we’d most likely use a mathematical function.

Angular Pipes and Pure Functions

In Angular, on the other hand, we have pipes. Pipes are used for performing some kind of data processing, for instance, data formatting. There are two types of pipes:

- Pure pipes - produce the same output when invoked with the same set of arguments. Such pipes hold the referential transparency property.

- Impure pipes - can hold state and respectively produce different output for the same set of arguments.

Examples of pure pipes are the DecimalPipe and DatePipe pipes. Every time when we invoke the DecimalPipe with given number and formatting configuration, we’ll always get the exact same string as a result.

An example for impure pipe is the async pipe for instance, which holds internal state. More about pure and impure pipes you can find in my book “Switching to Angular”.

Alright, so we have pure and impure pipes but how does this matter for Angular? Well:

Angular is going to evaluate given pure pipe call only if it has received different arguments compared to its previous invocation.

Angular is going to determine if the arguments of the pipe are different by performing an equality check. This means that, if we have:

{{ 2.718281828459045 | number:'3.1-5' }}

Angular is going to evaluate the expression once and produce the string 2.718. The next time when the change detection runs, Angular will get the last result from the evaluation since the arguments of the pure pipe haven’t changed!

Optimizing Expression Re-Evaluation with Pure Pipes

Wait, isn’t that exactly what we want to do in our application - do not re-evaluate the employee’s numeric value unless it gets changed? This means that we can encapsulate our business calculation inside of a pure pipe and as a bonus get the caching that Angular provides.

Here’s how we can proceed:

@Pipe({

name: 'calculate',

pure: true

})

export class CalculatePipe {

transform(num: number) {

return fibonacci(num);

}

}

In fact, all pipes in Angular are pure by default so we can drop the pure: true property.

Now we need to modify the template of the ListComponent a little bit to invoke the pipe instead of the calculate method defined inside of its controller:

@Component({

changeDetection: ChangeDetectionStrategy.OnPush,

template: `

...

{{ item.num | calculate }}

...

`

})

export class ListComponent { ... }

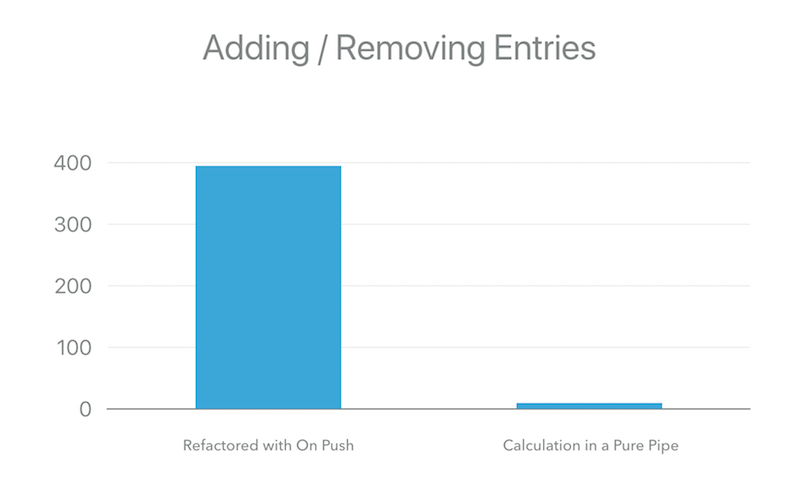

To verify if the last optimization improved the application’s performance. I wrote another e2e test which adds and removes employees from the sales department. After running it with benchpress, I got the following results:

With the latest optimization, the time required for running the tests dropped from 394.53ms to 9.70ms! That is a huge improvement! We achieved it only by performing a small refactoring, without writing any custom code, just taking advantage of what Angular already provides for free!

Initial Application Rendering

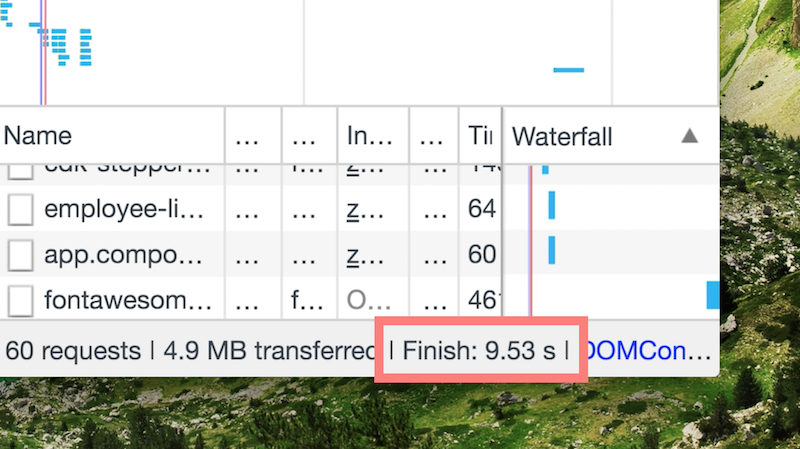

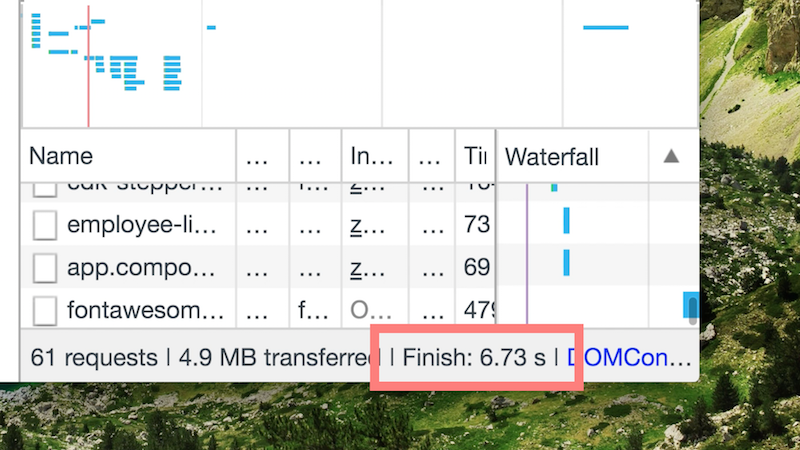

For this performance benchmark we’ll increase the number of items from 140 to 1,000. Lets see how this is going to affect our application’s rendering performance:

9.53s is quite a lot for initial rendering time. In fact…

Waiting for slow web pages to load is as stressful as watching a horror movie: https://t.co/spwEC1P9ct #perfmatters pic.twitter.com/3JmcGPZij2

— Addy Osmani (@addyosmani) March 19, 2016

In our case we’re even not waiting for the application to get loaded, we’re waiting for it to get rendered. Let’s suppose we have put a lot of effort into optimizing the network performance of the application and our bundle size is only 50KB, we download all the resources from the network for less than 100ms. This sounds great, right? Well, after that the user needs to wait another 9430ms in order see the application rendered.

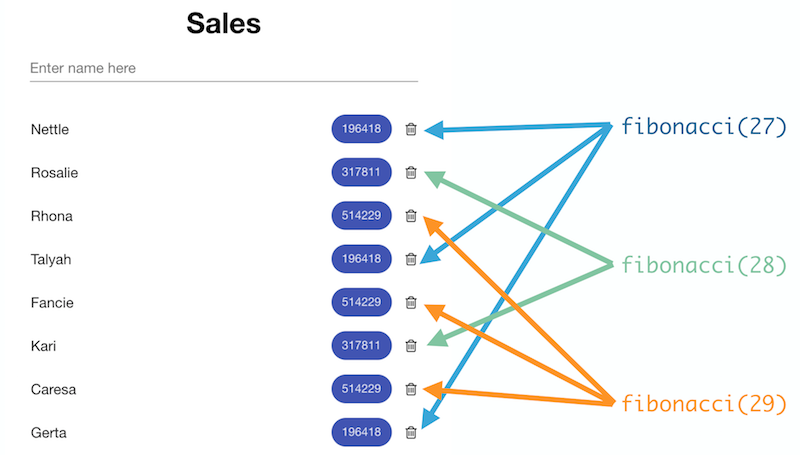

There are various techniques to fix this - we don’t have to render all the 1,000 employees at once, we can, for instance, apply pagination or render the items lazily when the user scrolls. But there’s also something else we can apply in this specific case. For this purpose, let’s take a look at the numeric data for the employees:

We have a lot of employees with the same numeric values which produce the same output after going through the business calculation. We can conclude that in this case, we have samples in a small range. Lets for a second remember what optimization Angular performs with pure pipes:

Angular is going to evaluate given pure pipe call only if it has received different arguments compared to its previous invocation.

This doesn’t say anywhere that Angular is not going to evaluate two pipe expressions in different places in the component tree which have the same arguments. So, if we have:

<md-list-item>

{{ 'Emily' }}

{{ 27 | calculate }}

</md-list-item>

<md-list-item>

{{ 'Dan' }}

{{ 27 | calculate }}

</md-list-item>

Angular is going to evaluate {{ 27 | calculate }} twice! The optimization that the framework will perform is that it won’t re-evaluate the expressions on the next tick of the change detection mechanism. This means that it’ll cache the result for the last value for a specific place in the rendered (dynamic) component tree.

On the other hand, in functional programming for pure functions, we can apply an optimization called memoization which Wikipedia defines as:

In computing, memoization or memoization is an optimization technique used primarily to speed up computer programs by storing the results of expensive function calls and returning the cached result when the same inputs occur again.

In contrast to the caching that Angular performs, memoization uses a global cache used for all the invocations of given function. This means that in the context of the example above if we apply memoization to the fibonacci function, although {{ 27 | calculate }} will be evaluated twice, fibonacci(27) will be invoked only once, the next time we’ll directly get the memoized result!

We can apply memoization to fibonacci using lodash.memoize:

const memoize = require('lodash.memoize');

const fibonacci = memoize((num: number): number => {

if (num === 1 || num === 2) return 1;

return fibonacci(num - 1) + fibonacci(num - 2);

});

Now lets see how this affects our initial rendering:

Not bad! By performing this optimization, we reduced the initial rendering with 30%!

Memoization, Pure Pipes, On Push and Referential Transparency

As we saw from the example above, we can think of pure pipes as pure functions. On the other hand, the optimization that Angular performs for pure pipes differs quite a lot compared to memoization. Angular treats expressions formed by pure pipes as referentially transparent expressions. Here’s definition of the property of referential transparency:

If all functions involved in the expression are pure functions, then the expression is referentially transparent. Also, some impure functions can be included in the expression if their values are discarded and their side effects are insignificant.

To what degree we consider the side effect performed by a pure pipe “insignificant” depends on our own judgment. In case we decide that the side effect that our pure pipe performs is significant, we can declare the pipe as impure by setting the pure property of the object literal we pass to the @Pipe decorator to false.

An interesting question to ask is, can we apply memoization to all pure pipes in order to get the performance benefit from the latest optimization we did? Here we can think of two cases:

- When the arguments of the pipe are primitive values.

- When the arguments of the pipe are non-primitive values.

For primitive values, it makes sense to apply memoization since we can create a cache which maps the pipe’s arguments to their results. Of course, this is only applicable in case the pure pipe performs no side effects or they are insignificant enough.

On the other hand, if the pipe has non-primitive arguments the situation can get trickier. In such case, it’ll be quite inconvenient to cache the result for the function based on its arguments’ references. Very often two instances of a data structure which have different references can hold the same data. Should we return the cached result in such case or not? Probably we should. But how can we efficiently determine if the items in the two collections are the same? Maybe hashing? This is a topic of another discussion and there is a lot of research in this direction.

For components, we can think similarly. We can abstract them as functions and consider their inputs as arguments, and the UI that they render as the function’s result. We think of the Angular templates as expressions and the components with OnPush change detection used in these templates as referentially transparent sub-expressions.

That’s how we found some patterns which are already well described by computer science in the face of pure functions, referential transparency, and memoization.

Conclusion

This blog post was the second from the series “Faster Angular Applications”.

In this part, we improved the operations for adding and removing employees from the lists by encapsulating the business computation inside of a pure pipe. After that we explained what optimizations Angular performs on pure pipes, treating the expressions that they form as referentially transparent.

As the next step, to optimize the initial rendering of our application, we used memoization.

Finally, we explained the theoretical foundation behind these APIs. It’s definitely worth it to invest time in computer science to understand the underlying concepts behind everything we use on a daily basis. This way we can find agnostic patterns across technologies and reuse them in our projects.

In conclusion, we can say that there’s no silver bullet for optimizing the runtime performance of our Angular applications. There are several techniques we can apply in response to our deep understanding of:

- The component structure of our applications.

- The business data that our application processes and visualizes.

On top of that, to conclude if the optimizations we do are meaningful, we should make application-specific benchmarks.