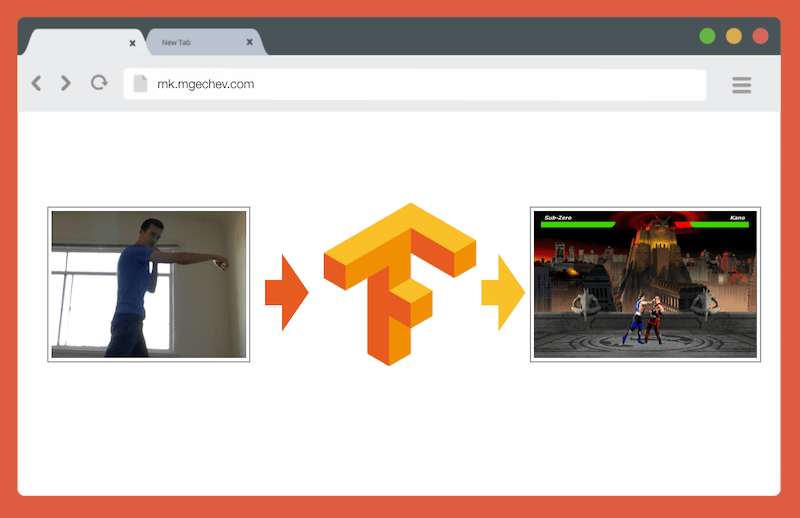

Playing Mortal Kombat with TensorFlow.js. Transfer learning and data augmentation

Edit · Oct 20, 2018 · 25 minutes read · Follow @mgechev

While experimenting with enhancements of the prediction model of Guess.js, I started looking at deep learning. I’ve focused mainly on recurrent neural networks (RNNs), specifically LSTM because of their “unreasonable effectiveness” in the domain of Guess.js. In the same time, I started playing with convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which although less traditionally, are also often used for time series. CNNs are usually used for image classification, recognition, and detection.

After playing around with CNNs, I remembered an experiment I did a few years ago, when the browser vendors introduced the getUserMedia API. In this experiment, I used the user’s camera as a controller for playing a small JavaScript clone of Mortal Kombat 3. You can find the game at my GitHub account. As part of the experiment, I implemented a basic posture detection algorithm which classifies an image into the following classes:

- Upper punch with the left and right hands

- Kick with the left and right legs

- Walking left and right

- Squatting

- None of the above

The algorithm is so simple that I’d be able to explain it in a few sentences:

The algorithm takes a snapshot of the background behind the user. Once the user enters the scene, the algorithm was finding the difference between the original, background frame, and the current frame with the user inside of it. This way, it’s able to detect where the user’s body is. As a next step, the algorithm renders the user’s body with white on a black canvas. After that, it builds a vertical and horizontal histogram summing the values for each pixel. Based on the aggregated calculation, the algorithm detects what the current user posture is.

You can find demo of the implementation in the video below. The source code is at my GitHub account.

Although I had success with controlling my tiny MK clone, the algorithm was far from perfect. It requires a frame with the background behind the user. For the detection procedure to work correctly, the background frame needs to be with the same color throughout the execution of the program. Such restriction means that changes in the light, shadows, etc., would introduce disturbance and inaccurate results. Finally, the algorithm does not recognize actions - based on a background frame; it classifies another frame as a posture from a predefined set.

Now, given the advancements in the Web platform APIs, and more specifically WebGL, I decided to give the problem another shot by using TensorFlow.js.

Introduction

In this blog post, I’ll share my experience of building a posture classification algorithm using TensorFlow.js and MobileNet. In the process, we’ll look at the following topics:

- Collecting training data for image classification

- Performing data augmentation using imgaug

- Transfer learning with MobileNet

- Binary classification and n-ary classification

- Training an image classification TensorFlow.js model in Node.js and using it in the browser

- Few words on using action classification with LSTM

For this article, we’ll relax the problem to posture detection based on a single frame, in contrast to recognizing an action from a sequence of frames. We’ll develop a supervised deep learning model, which based on an image from the user’s laptop camera, indicates if on this image the user is punching, kicking, or not doing the first two.

By the end of the article, we’d be able to build a model for playing MK.js:

To get most of this article, the reader should have a familiarity with fundamental concepts from software engineering and JavaScript. Basic understanding of deep learning would be helpful but not strictly required.

Collecting Data

The accuracy of a deep learning model depends to a very great extent on the quality of the training data. We should aim for a rich training set similar to the inputs that we’ll get in the production system.

Our model should be able to recognize punches and kicks. This means that we should collect images from three different categories:

- Punches

- Kicks

- Others

For this experiment, I collected photos with the help of two volunteers (@lili_vs and @gsamokovarov). We recorded 5 videos with QuickTime on my MacBook Pro, each of which contains 2-4 punches and 2-4 kicks.

Now, since we need images but instead we have mov videos, we can use ffmpeg, to extract the individual frames and store them as jpg pictures:

ffmpeg -i video.mov $filename%03d.jpg

To run the above command, you may first need to install ffmpeg on your computer.

If we want to train the model, we have to provide inputs and their corresponding outputs, but at this step, we have a bunch of images of three people taking different poses. To structure our data, we have to categorize the frames from the videos that we extracted in the three categories above - punches, kicks, others. For each category, we can create a separate directory and move all the corresponding images there.

This way, in each directory we should have roughly about 200 images, similar to the ones below:

Note that in the directory “Others” we may have many more images because there are fewer photos of punches and kick then ones of people walking, turning around, or managing the video recording. If we have too many images from one class and we train the model on all of them, we risk making it biased towards this specific class. So, even if we try to classify an image of a person punching, the neural network is likely going to output the class “Others.” To reduce this bias, we can delete some of the photos from the “Others” directory and train the model with an equal number of images from each category.

For convenience, we’ll name the images in the individual directories after the numbers from 1 to 190, so the first image would be 1.jpg, the second 2.jpg, etc.

If we train the model with only 600 photos taken in the same environment, with the same people, we’ll not be able to achieve a very high level of accuracy. To extract as much value as possible from our data, we can generate some extra samples by using data augmentation.

Data Augmentation

Data augmentation is a technique which allows us to increase the number of data points by synthesizing new ones from the existing dataset. Usually, we use data augmentation for increasing the size and the variety of our training set. We’d pass the original images to a pipeline of transformations which produce new images. We should not be too aggressive with the transformations - applying them on an image classified as a punch, should produce other images classifiable as punches.

Valid transformations over our images would be a rotation, inverting the colors, blurring the images, etc. There are great open source tools for image data augmentation available online. At the moment of writing, there are no rich alternatives in JavaScript, so I used a library implemented in Python - imgaug. It contains a set of augmenters that can be applied probabilistically.

Here’s the data augmentation logic that I applied in this experiment:

np.random.seed(44)

ia.seed(44)

def main():

for i in range(1, 191):

draw_single_sequential_images(str(i), "others", "others-aug")

for i in range(1, 191):

draw_single_sequential_images(str(i), "hits", "hits-aug")

for i in range(1, 191):

draw_single_sequential_images(str(i), "kicks", "kicks-aug")

def draw_single_sequential_images(filename, path, aug_path):

image = misc.imresize(ndimage.imread(path + "/" + filename + ".jpg"), (56, 100))

sometimes = lambda aug: iaa.Sometimes(0.5, aug)

seq = iaa.Sequential(

[

iaa.Fliplr(0.5), # horizontally flip 50% of all images

# crop images by -5% to 10% of their height/width

sometimes(iaa.CropAndPad(

percent=(-0.05, 0.1),

pad_mode=ia.ALL,

pad_cval=(0, 255)

)),

sometimes(iaa.Affine(

scale={"x": (0.8, 1.2), "y": (0.8, 1.2)}, # scale images to 80-120% of their size, individually per axis

translate_percent={"x": (-0.1, 0.1), "y": (-0.1, 0.1)}, # translate by -10 to +10 percent (per axis)

rotate=(-5, 5),

shear=(-5, 5), # shear by -5 to +5 degrees

order=[0, 1], # use nearest neighbour or bilinear interpolation (fast)

cval=(0, 255), # if mode is constant, use a cval between 0 and 255

mode=ia.ALL # use any of scikit-image's warping modes (see 2nd image from the top for examples)

)),

iaa.Grayscale(alpha=(0.0, 1.0)),

iaa.Invert(0.05, per_channel=False), # invert color channels

# execute 0 to 5 of the following (less important) augmenters per image

# don't execute all of them, as that would often be way too strong

iaa.SomeOf((0, 5),

[

iaa.OneOf([

iaa.GaussianBlur((0, 2.0)), # blur images with a sigma between 0 and 2.0

iaa.AverageBlur(k=(2, 5)), # blur image using local means with kernel sizes between 2 and 5

iaa.MedianBlur(k=(3, 5)), # blur image using local medians with kernel sizes between 3 and 5

]),

iaa.Sharpen(alpha=(0, 1.0), lightness=(0.75, 1.5)), # sharpen images

iaa.Emboss(alpha=(0, 1.0), strength=(0, 2.0)), # emboss images

iaa.AdditiveGaussianNoise(loc=0, scale=(0.0, 0.01*255), per_channel=0.5), # add gaussian noise to images

iaa.Add((-10, 10), per_channel=0.5), # change brightness of images (by -10 to 10 of original value)

iaa.AddToHueAndSaturation((-20, 20)), # change hue and saturation

# either change the brightness of the whole image (sometimes

# per channel) or change the brightness of subareas

iaa.OneOf([

iaa.Multiply((0.9, 1.1), per_channel=0.5),

iaa.FrequencyNoiseAlpha(

exponent=(-2, 0),

first=iaa.Multiply((0.9, 1.1), per_channel=True),

second=iaa.ContrastNormalization((0.9, 1.1))

)

]),

iaa.ContrastNormalization((0.5, 2.0), per_channel=0.5), # improve or worsen the contrast

],

random_order=True

)

],

random_order=True

)

im = np.zeros((16, 56, 100, 3), dtype=np.uint8)

for c in range(0, 16):

im[c] = image

for im in range(len(grid)):

misc.imsave(aug_path + "/" + filename + "_" + str(im) + ".jpg", grid[im])

The script above has a main method which has three for loops - one for each image category. In each iteration, in each of the loops, we invoke the method draw_single_sequential_images with the image name as the first argument, the path to the image as the second, and third argument the directory where the function should store the augmented images.

After that, we read the image from the disk and apply a set of transformations to it. I’ve documented most of the transformations in the snippet above, so we’ll not stop on them here.

For each image in the existing data set, the transformations produce 16 other images. Here’s an example of how the augmented images would look like:

Notice that in the script above, we scale the images to 100x56 pixel. We do this to reduce the amount of data, and respectively the amount of computations which our model would have to perform during training and evaluation.

Building the Model

Now let’s build the classification model!

Since we’re dealing with images, we’re going to use a convolutional neural network (CNN). This network architecture is known to be suitable for image recognition, object detection, and classification.

Transfer Learning

The figure below shows VGG-16, a popular CNN which is used for classification of images.

The VGG-16 network recognizes 1000 classes of images. It has 16 layers (we don’t count the output and the pooling layers). Such a multilayer network would be hard to train in practice. It’ll require a large dataset and many hours of training.

The hidden layers in a trained CNN recognize different features of the images from its training set starting from edges, going to more advanced features, such as shapes, individual objects, and so on. A trained CNN, similar to VGG-16, which recognizes a large set of images would have hidden layers that have discovered many features from its training set. Such features would be in common between most images, and respectively, reusable across different tasks.

Transfer learning allows us to reuse an already existing and trained network. We can take the output from any of the layers of the existing network and feed it as an input to a new neural network. This way, by training the newly created neural network, over time it can be taught to recognize new higher level features and correctly classify images from classes that the source model has never seen before.

For our purposes, we’ll use the MobileNet neural network, from the @tensorflow-models/mobilenet package. MobileNet is as powerful as VGG-16, but it’s also much smaller which makes its forward propagation faster and reduces its load time in the browser. MobileNet has been trained on the ILSVRC-2012-CLS image classification dataset.

You can give MobileNet a try in the widget below. Feel free to select an image from your file system or use your camera as an input:

Two of the choices that we have when we develop a model using transfer learning are:

- The output from which layer of the source model are we going to use as an input for the target model

- How many layers from the target model do we want to train, if any

The first point is quite essential. Depending on the layer we choose, we’re going to get features on lower or higher level of abstraction, as input to our neural network.

For our purposes, we’re not going to train any layers from MobileNet. We’re going to pick the output from global_average_pooling2d_1 and pass it as an input to our tiny model. Why did I pick this specific layer? Empirically. I did a few tests, and this layer was performing reasonably well.

Defining the Model

The original problem was to categorize an image in three classes - punch, kick, and other. Let us first solve a smaller problem - detect if the user is punching on a frame or not. This task is a typical binary classification problem. For the purpose, we can define the following model:

import * as tf from '@tensorflow/tfjs';

const model = tf.sequential();

model.add(tf.layers.inputLayer({ inputShape: [1024] }));

model.add(tf.layers.dense({ units: 1024, activation: 'relu' }));

model.add(tf.layers.dense({ units: 1, activation: 'sigmoid' }));

model.compile({

optimizer: tf.train.adam(1e-6),

loss: tf.losses.sigmoidCrossEntropy,

metrics: ['accuracy']

});

The snippet above defines a simple model with a layer with 1024 units and ReLU activation, and one output unit which goes through a sigmoid activation function. The sigmoid would produce a number between 0 and 1, depending on the probability the user to be punching at the given frame.

Why did I pick 1024 units for the second layer and 1e-6 learning rate? Well, I tried a couple of different options and saw that 1024 and 1e-6 work best. “Trying and seeing what” may don’t sound like the best approach but that’s pretty much how the tunning of hyperparameters in deep learning works - based on our understanding of the model we use our intuition to update orthogonal parameters and empirically check if the model performs well.

The compile method, compiles the layers together, preparing the model for training and evaluation. Here we declare that we want to use adam as an optimization algorithm. We also declare that we want to compute the loss with sigmoid cross entropy and we specify that we want to evaluate the model’s accuracy. TensorFlow.js calculates the accuracy with the formula:

Accuracy = (True Positives + True Negatives) / (Positives + Negatives)

If we want to apply transfer learning with MobileNet as a source model, we’ll first need to load it. Because it wouldn’t be practical to train our model with over 3k images in the browser, we’ll use Node.js and load the network from a file.

You can download MobileNet from here. In the directory, you can find model.json file, which contains the architecture of the model - layers, activations, etc. The rest of the files contain the model’s parameters. You can load the model from the file using:

export const loadModel = async () => {

const mn = new mobilenet.MobileNet(1, 1);

mn.path = `file://PATH/TO/model.json`;

await mn.load();

return (input): tf.Tensor1D =>

mn.infer(input, 'global_average_pooling2d_1')

.reshape([1024]);

};

Notice that in the loadModel method we return a function, which accepts a single dimensional tensor as an input and returns mn.infer(input, Layer). The infer method of MobileNet accepts as an argument input tensor and a layer. The layer specifies from which hidden layer we’d want to get the output from. If you open model.json and search for global_average_pooling2d_1 you’ll find it as the name of one of the layers.

Now, to train this model, we’ll have to create our training set. For the purpose, we’ll have to pass each one of our images through the infer method of MobileNet and associate a label with it - 1 for images which contain a punch, and 0 for images without a punch:

const punches = require('fs')

.readdirSync(Punches)

.filter(f => f.endsWith('.jpg'))

.map(f => `${Punches}/${f}`);

const others = require('fs')

.readdirSync(Others)

.filter(f => f.endsWith('.jpg'))

.map(f => `${Others}/${f}`);

const ys = tf.tensor1d(

new Array(punches.length).fill(1)

.concat(new Array(others.length).fill(0)));

const xs: tf.Tensor2D = tf.stack(

punches

.map((path: string) => mobileNet(readInput(path)))

.concat(others.map((path: string) => mobileNet(readInput(path))))

) as tf.Tensor2D;

In the snippet above, first we read the files in the directory containing pictures of punches, and the one with other images. After that, we define a one-dimensional tensor which contains the output labels. If we have n images with a punch and m other images, the tensor would have n elements with value 1 and m elements with value 0.

In xs we stack the results from the invocation of the infer method of MobileNet for the individual images. Notice that for each image we invoke the readInput method. Let us take a look at its implementation:

export const readInput = img => imageToInput(readImage(img), TotalChannels);

const readImage = path => jpeg.decode(fs.readFileSync(path), true);

const imageToInput = image => {

const values = serializeImage(image);

return tf.tensor3d(values, [image.height, image.width, 3], 'int32');

};

const serializeImage = image => {

const totalPixels = image.width * image.height;

const result = new Int32Array(totalPixels * 3);

for (let i = 0; i < totalPixels; i++) {

result[i * 3 + 0] = image.data[i * 4 + 0];

result[i * 3 + 1] = image.data[i * 4 + 1];

result[i * 3 + 2] = image.data[i * 4 + 2];

}

return result;

};

readInput first invokes the function readImage and after that delegates its invocation to imageToInput. readImage reads the image from the disk and after that decodes the buffer as a jpg image using the jpeg-js package. In imageToInput we transform the image into a three-dimensional tensor.

In the end, for each i from 0 to TotalImages, we should have ys[i] is 1 if xs[i] corresponds to an image with a punch, and 0 otherwise.

Training the Model

Now we are ready to train the model! For the purpose, invoke the method fit of the model’s instance:

await model.fit(xs, ys, {

epochs: Epochs,

batchSize: parseInt(((punches.length + others.length) * BatchSize).toFixed(0)),

callbacks: {

onBatchEnd: async (_, logs) => {

console.log('Cost: %s, accuracy: %s', logs.loss.toFixed(5), logs.acc.toFixed(5));

await tf.nextFrame();

}

}

});

The code above invokes fit with three arguments - xs, ys, and a configuration object. In the configuration object, we’ve set for how many epochs we want to train the model, we’ve provided a batch size, and a callback which TensorFlow.js would invoke after each batch.

The batch size determines with how large subsets of xs and ys we’ll train our model within one epoch. For each epoch, TensorFlow.js would pick a subset of xs and the corresponding elements from ys, it’ll perform forward propagation, get the output from the layer with sigmoid activation and after that, based on the loss, it’ll perform optimization using the adam algorithm.

Once you run the training script, you should see output similar to the one below:

Cost: 0.84212, accuracy: 1.00000

eta=0.3 >---------- acc=1.00 loss=0.84 Cost: 0.79740, accuracy: 1.00000

eta=0.2 =>--------- acc=1.00 loss=0.80 Cost: 0.81533, accuracy: 1.00000

eta=0.2 ==>-------- acc=1.00 loss=0.82 Cost: 0.64303, accuracy: 0.50000

eta=0.2 ===>------- acc=0.50 loss=0.64 Cost: 0.51377, accuracy: 0.00000

eta=0.2 ====>------ acc=0.00 loss=0.51 Cost: 0.46473, accuracy: 0.50000

eta=0.1 =====>----- acc=0.50 loss=0.46 Cost: 0.50872, accuracy: 0.00000

eta=0.1 ======>---- acc=0.00 loss=0.51 Cost: 0.62556, accuracy: 1.00000

eta=0.1 =======>--- acc=1.00 loss=0.63 Cost: 0.65133, accuracy: 0.50000

eta=0.1 ========>-- acc=0.50 loss=0.65 Cost: 0.63824, accuracy: 0.50000

eta=0.0 ==========>

293ms 14675us/step - acc=0.60 loss=0.65

Epoch 3 / 50

Cost: 0.44661, accuracy: 1.00000

eta=0.3 >---------- acc=1.00 loss=0.45 Cost: 0.78060, accuracy: 1.00000

eta=0.3 =>--------- acc=1.00 loss=0.78 Cost: 0.79208, accuracy: 1.00000

eta=0.3 ==>-------- acc=1.00 loss=0.79 Cost: 0.49072, accuracy: 0.50000

eta=0.2 ===>------- acc=0.50 loss=0.49 Cost: 0.62232, accuracy: 1.00000

eta=0.2 ====>------ acc=1.00 loss=0.62 Cost: 0.82899, accuracy: 1.00000

eta=0.2 =====>----- acc=1.00 loss=0.83 Cost: 0.67629, accuracy: 0.50000

eta=0.1 ======>---- acc=0.50 loss=0.68 Cost: 0.62621, accuracy: 0.50000

eta=0.1 =======>--- acc=0.50 loss=0.63 Cost: 0.46077, accuracy: 1.00000

eta=0.1 ========>-- acc=1.00 loss=0.46 Cost: 0.62076, accuracy: 1.00000

eta=0.0 ==========>

304ms 15221us/step - acc=0.85 loss=0.63

Notice how over time the accuracy increases and the loss decreases.

With my dataset, after the model’s training completed I reached 92% accuracy. Below, you can find a widget where you can play with the pre-trained model. You can select an image from your computer, or take one with your camera and classify it as a punch or not.

Keep in mind that the accuracy might not be very high because of the small training set that I had available.

Running the Model in the Browser

In the last section, we trained a model for a binary classification. Now let us run it in the browser and wire it up together with MK.js!

const video = document.getElementById('cam');

const Layer = 'global_average_pooling2d_1';

const mobilenetInfer = m => (p): tf.Tensor<tf.Rank> => m.infer(p, Layer);

const canvas = document.getElementById('canvas');

const scale = document.getElementById('crop');

const ImageSize = {

Width: 100,

Height: 56

};

navigator.mediaDevices

.getUserMedia({

video: true,

audio: false

})

.then(stream => {

video.srcObject = stream;

});

In the snippet above, we have few declarations:

video- contains a reference to the HTML5 video element on the pageLayer- contains the name of the layer from MobileNet that we want to get the output from and pass it as an input to our modelmobilenetInfer- is a function which accepts an instance of MobileNet and returns another function. The returned function accepts input and returns the corresponding output from the specified layer of MobileNetcanvas- points to an HTML5 canvas element that we’ll use to extract frames from the videoscale- is another canvas that we’ll use to scale the individual frames

After that, we get a video stream from the user’s camera and set it as a source of the video element.

As next step, we’ll implement a grayscale filter which accepts a canvas and transforms its content:

const grayscale = (canvas: HTMLCanvasElement) => {

const imageData = canvas.getContext('2d').getImageData(0, 0, canvas.width, canvas.height);

const data = imageData.data;

for (let i = 0; i < data.length; i += 4) {

const avg = (data[i] + data[i + 1] + data[i + 2]) / 3;

data[i] = avg;

data[i + 1] = avg;

data[i + 2] = avg;

}

canvas.getContext('2d').putImageData(imageData, 0, 0);

};

As a next step, let us wire the model together with MK.js:

let mobilenet: (p: any) => tf.Tensor<tf.Rank>;

tf.loadModel('http://localhost:5000/model.json').then(model => {

mobileNet

.load()

.then((mn: any) => mobilenet = mobilenetInfer(mn))

.then(startInterval(mobilenet, model));

});

In the code above, first, we load the model that we trained above and after that load MobileNet. We pass MobileNet to the mobilenetInfer method so that we can get a shortcut for calculating the output from the hidden layer of the network. After that, we invoke the startInterval method with the two networks as arguments.

const startInterval = (mobilenet, model) => () => {

setInterval(() => {

canvas.getContext('2d').drawImage(video, 0, 0);

grayscale(scale

.getContext('2d')

.drawImage(

canvas, 0, 0, canvas.width,

canvas.width / (ImageSize.Width / ImageSize.Height),

0, 0, ImageSize.Width, ImageSize.Height

));

const [punching] = Array.from((

model.predict(mobilenet(tf.fromPixels(scale))) as tf.Tensor1D)

.dataSync() as Float32Array);

const detect = (window as any).Detect;

if (punching >= 0.4) detect && detect.onPunch();

}, 100);

};

startInterval is where the fun happens! First, we start an interval, where every 100ms we invoke an anonymous function. In this function, we first render the video on top of the canvas which contains our current frame. After that, we scale down the frame to 100x56 and apply a grayscale filter to it.

As a next step, we pass the scaled frame to MobileNet, we get the output from the desired hidden layer and pass it as an input to the predict method of our model. The predict method of our model returns a tensor with a single element. By using dataSync we get the value from the tensor and set assign it to the constant punching.

Finally, we check if the probability for the user to be punching on this frame is over 0.4 and depending on this, we invoke the onPunch method of the global object Detect. MK.js exposes a global object with three methods: onKick, onPunch, and onStand, which we can use to control one of the characters.

That’s it! 🎉 Here’s the result!

Recognizing Kicks and Punches with N-ary Classification

In the next section of this blog post, we’ll make a smarter model - we’ll develop a neural network which recognizes punches, kicks, and other images. Let us this time start with the process of preparing the training set:

const punches = require('fs')

.readdirSync(Punches)

.filter(f => f.endsWith('.jpg'))

.map(f => `${Punches}/${f}`);

const kicks = require('fs')

.readdirSync(Kicks)

.filter(f => f.endsWith('.jpg'))

.map(f => `${Kicks}/${f}`);

const others = require('fs')

.readdirSync(Others)

.filter(f => f.endsWith('.jpg'))

.map(f => `${Others}/${f}`);

const ys = tf.tensor2d(

new Array(punches.length)

.fill([1, 0, 0])

.concat(new Array(kicks.length).fill([0, 1, 0]))

.concat(new Array(others.length).fill([0, 0, 1])),

[punches.length + kicks.length + others.length, 3]

);

const xs: tf.Tensor2D = tf.stack(

punches

.map((path: string) => mobileNet(readInput(path)))

.concat(kicks.map((path: string) => mobileNet(readInput(path))))

.concat(others.map((path: string) => mobileNet(readInput(path))))

) as tf.Tensor2D;

Just like before, first we read the directories containing punches, kicks, and other images. After that, compared to the previous section, we form the expected output as a two-dimensional tensor, instead of one-dimensional. If we have n images of punches, m images of kicks, and k other images, the ys tensor would have n elements with value [1, 0, 0], m elements with value [0, 1, 0], and k elements with value [0, 0, 1]. With the images corresponding to a punch we associate the vector [1, 0, 0], with the images corresponding to a kick we associate the vector [0, 1, 0], and finally, with the other images we associate the vector [0, 0, 1].

A vector with n elements, which has n - 1 elements with value 0 and 1 element with value 1, we call a one-hot vector.

After that, we form the input tensor xs by stacking the outputs for each image from MobileNet.

For the purpose, we’ll have to update the model definition:

const model = tf.sequential();

model.add(tf.layers.inputLayer({ inputShape: [1024] }));

model.add(tf.layers.dense({ units: 1024, activation: 'relu' }));

model.add(tf.layers.dense({ units: 3, activation: 'softmax' }));

await model.compile({

optimizer: tf.train.adam(1e-6),

loss: tf.losses.sigmoidCrossEntropy,

metrics: ['accuracy']

});

The only two differences from the previous model are:

- Number of units in the output layer

- Activation in the output layer

The reason why we have 3 units in the output layer is that we have three different categories of images:

- Punching

- Kicking

- Others

The softmax activation invoked on top of these 3 units transforms their parameters to a tensor with 3 values. Why do we have 3 units in the output layer? We know that we can represent 3 values (one for each of our 3 classes) with 2 bits - 00, 01, 10. The sum of the values of the tensor produced by softmax equals 1, which means that we’ll never get 00, so we’ll never be able to classify images from one of the classes.

After I trained the model for 500 epochs, I achieved about 92% accuracy! That’s not bad, but don’t forget that the training was on top of a small dataset.

The next step is to run the model in the browser! Since the logic for this is quite similar to running the model for binary classification, let us take a look at the last step, where we pick an action based on the model’s output:

const [punch, kick, nothing] = Array.from((model.predict(

mobilenet(tf.fromPixels(scaled))

) as tf.Tensor1D).dataSync() as Float32Array);

const detect = (window as any).Detect;

if (nothing >= 0.4) return;

if (kick > punch && kick >= 0.35) {

detect.onKick();

return;

}

if (punch > kick && punch >= 0.35) detect.onPunch();

Initially, we invoke MobileNet with the scaled, grayscaled canvas, after that we pass the output to our trained model. The model returns a one-dimensional tensor that we convert to Float32Array with dataSync. As a next step, by using Array.from we cast the typed array to a JavaScript array, and we extract the probabilities the pose on the frame to be a punch, kick, or none the last two.

If the probability the pose of being neither a kick nor a punch is higher than 0.4 we return. Otherwise, if we have a higher probability for the frame to show a kick, and this probability is higher than 0.32 we emit a kick command to MK.js. If the probability of a punch is over 0.32 and is higher than the probability for a kick, then we emit a punch action.

That’s pretty much all of it! You can now see the result below:

Now you can play with the subsequent widget which uses the trained model over input from a file you selected, or a snapshot from your camera. Try it out with an image of you punching or kicking!

Action Recognition

If we collect a large and diverse dataset of people punching and kicking, we’ll be able to build a model which performs excellently on individual frames. However, is this enough? What if we want to go one step further and distinguish two different types of kicks - roundhouse kick from a back kick.

As we can see from the snapshots below, both kicks would look similar at given point in time, from a certain angle:

But if we look at the execution, the movements are quite different:

So, how do we teach our neural network to look into a sequence of frames, instead of a single one?

For the purpose, we can explore a different class of neural networks called Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs). RNNs are excellent for dealing with time series, for example:

- Natural language processing (NLP) where one word depends on the ones before and after

- Predicting which page the user would visit next based on their navigation history

- Recognizing an action from a sequence of frames

Implementing such a model is out of the scope of this article but let us take a look at a sample architecture so we can get an intuition for how everything would work together!

The Power of RNNs

On the image below, you can find a diagram which shows a model for action recognition:

We take the last n frames from a video and pass them to a CNN. The output of the CNN for each frame, we pass as input to the RNN. The recurrent neural network would figure out the dependencies between the individual frames and recognize what action they encode.

Conclusion

In this article, we developed a model for image classification. For the purpose, we collected a dataset by extracting video frames and by hand, dividing them among three separate categories. As a next step, we generated additional data using image augmentation with imgaug.

After that, we explained what’s transfer learning and how we can take advantage of it by reusing the trained model MobileNet from the package @tensorflow-models/mobilenet. We loaded MobileNet from a file in a Node.js process and trained an additional dense layer which we fed with the output from a hidden layer of MobileNet. After going through the training process, we achieved over 90% accuracy!

To use the model we developed in the browser, we loaded it together with MobileNet and started categorizing frames from the user’s camera every 100ms. We connected the model with the game MK.js and used the output of the model to control one of the characters.

Finally, we looked at how we can improve our model even further by combining it with a recurrent neural network for action recognition.

I hope you enjoyed this tiny project as much as I did! 🙇🏼