Since Angular version 8, we support dynamic imports in loadChildren in the route declaration. In this article, I want to give more information about why dynamic imports could be tricky to handle from tooling perspective and why you should be careful with them.

As engineers, we often have the perception that dynamic == good. With statically typed languages, such as TypeScript, this has shifted over the years. Because of compile-time checking, more folks started appreciating what tooling can give us if we provide statically analyzable information at build time.

In the past, I’ve heard a lot of complaints around the static imports in JavaScript:

Why does JavaScript restricts us to use only string literals when specifying the module in ES2015 imports?

To see what are the benefits of this, let’s look at an example:

import { foo } from './bar';

Above we have the import keyword, import specifier ({ foo }), from keyword, followed by the ./bar string literal. There are two great things about this construct:

- Statically we can determine what symbols we import

- Statically we can determine from which module we import

Static vs. Dynamic Analysis

It’s essential to understand what I mean by saying statically. In practice, any correct program can be partially executed at build time (for example, by webpack, prepack, etc.) and, potentially, fully executed at runtime (if we have sufficient information, and of course, this does not imply that the program will ever terminate). Look at this example:

const fib = n => n === 1 || n === 2 ? 1 : fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

console.log(fib(5));

If we add a prepack plugin to our webpack build, the final bundle will look something like this:

console.log(5);

Which means that our users will directly see 5 in the console, without having to execute the fib function. This is only possible because our program does not use data which is only available at runtime. For example:

const fib = n => n === 1 || n === 2 ? 1 : fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

console.log(fib(window.num));

The evaluation of the snippet above would be impossible at build time because we don’t know what’s the value of window.num (imagine we rely on a Chrome extension to set the window.num property).

How does this relate to ES2015 imports? It connects in at least two different ways. With ES2015 imports we can:

- Statically analyze the import specifier when the imported symbols are explicitly listed

- Statically analyze the path because it’s a string literal

Let’s suppose for a second that this is a valid syntax:

import { foo } from getPath();

The implementation of getPath could involve information which is only available at runtime, for example, we can read a property from localStorage, send a sync XHR, etc. The ECMAScript standard allows only string literals so that the bundler or the browser, can know the exact location of the module we’re importing from.

Now, let’s look at another example:

import * as foo from './foo';

We specify the path as a string literal but we use a wildcard import. In this scenario, in the general case the bundler will be unable to determine which symbols from ./foo we use in the current module. Imagine we have the following snippet:

// foo.js

export const a = 42;

export const b = 1.618;

export const c = a + b;

// bar.js

import * as foo from './foo';

console.log(foo.a);

console.log(foo[localStorage.get('bar')]);

If we invoke the bundler by specifying bar.js as an entry point, statically we can determine that bar.js uses a but we have no idea if b and c are going to be needed at runtime, we don’t know what the value of localStorage.get('bar') is. This way we won’t be able to get rid of the unused symbols since we don’t know what symbols from foo.js its consumers use.

That’s why I often discourage people to use wildcard imports since they could block the bundler from tree-shaking effectively.

What about dynamic imports

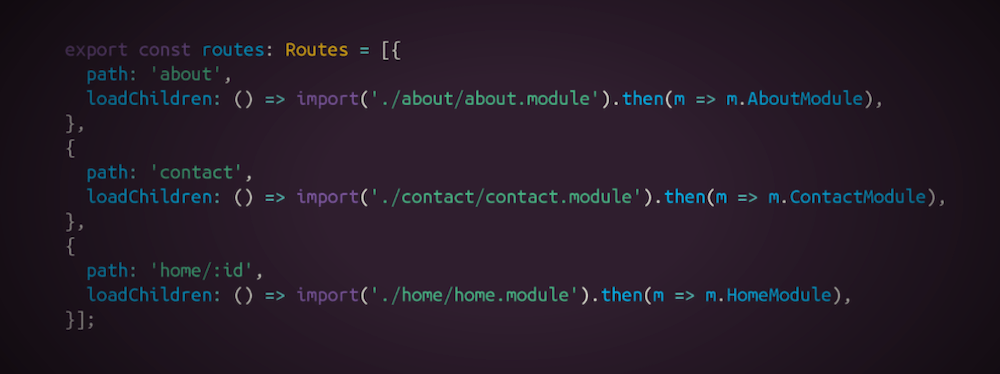

Originally, I started writing this article to explain why dynamic imports could be tricky from a tooling perspective. Let’s suppose that we have a lazy-loaded module:

// dynamic.js

export const a = 42;

// foo.js

import('./dynamic.js').then(m => console.log(m.a));

If we try to bundle this with rollup by specifying foo.js as an entry point we’ll get something like:

$ rollup foo.js --output.format esm

foo.js → stdout...

//→ foo.js:

import('./chunk-75df839a.js').then(m => console.log(m.a));

//→ chunk-75df839a.js:

const a = 42;

export { a };

created stdout in 59ms

Here’s what rollup did:

- Created a chunk from

foo.js, bundling it with all of its static imports (in this case there are none) - Statically analyzed

foo.jsand found that it dynamically importsdynamic.js - Created another chunk called

chunk-75df839a.jsby bundling togetherdynamic.jswith all its static imports (in this case there are none)

Now let’s change something in foo.js:

// foo.js

import('./dynamic.js' + '').then(m => console.log(m.a));

In this case, we get:

$ rollup foo.js --output.format esm

foo.js → stdout...

import('./dynamic.js' + '').then(m => console.log(m.a));

created stdout in 39ms

This means that rollup was not able to correctly figure out the entry point of the dynamically loaded chunk. Why? We changed the argument of the import from a string literal to an expression. Same, will happen if we use an expression which could be only evaluated at runtime (for example, import(localStorage.getItem('foo'))). Webpack would handle this case because it’ll try to evaluate the expression statically, at build time:

$ webpack foo.js

Hash: 2a1d2bcb0c5277c3bf29

Version: webpack 4.30.0

Time: 396ms

Built at: 05/11/2019 3:44:22 PM

Asset Size Chunks Chunk Names

1.js 141 bytes 1 [emitted]

main.js 2 KiB 0 [emitted] main

Entrypoint main = main.js

[0] ./foo.js 58 bytes {0} [built]

[1] ./dynamic.js 21 bytes {1} [built]

Dynamic Imports and TypeScript

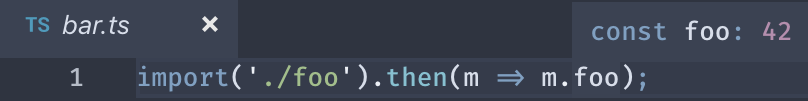

Now, let’s look at another example using TypeScript. Let’s suppose we have the following snippet:

// foo.ts

export const foo = 42;

// bar.ts

import('./foo').then(m => m.foo);

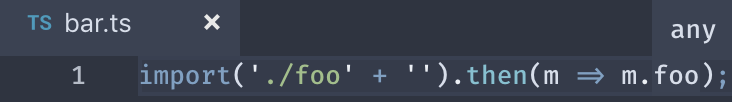

If we open bar.ts in a text editor and we point over m.foo, we’ll see that it’s of type number. This means that TypeScript’s type inference has tracked the reference and figured out its type. Now, change bar.ts to:

// bar.ts

import('./foo' + '').then(m => m.foo);

If we point over m.foo again, we’ll find out that it has type any (TypeScript version 3.1.3). Why both differ? When TypeScript finds out that we’ve passed a string literal to the dynamic import it follows the module reference and performs type inference; if it finds an expression, it fallbacks to type any.

Let’s go through a quick recap of our observations:

- In the general case, dynamic imports cannot be tree-shaken because we can access the exported symbols with index signature with an expression that contains data only available at runtime (i.e.

import(...).then(m => m[localStorage.getItem('foo')])) - Modern bundlers and TypeScript can resolve dynamic imports only when we have specified the module with a string literal (an exception is webpack, which statically performs partial evaluation)

This is one of the reasons why in the general case Guess.js, cannot handle dynamic imports and map them directly to Google Analytics URLs so that it can reuse the predictive model at runtime.

Conclusions

Dynamic imports are fantastic for code-splitting on a granular level. They allow us to provide lazy-loading boundaries in our application. In the same time, because of their dynamical nature, they often will enable us to sneak in code that requires runtime data for resolution of the imported module, or for accessing its exports.

In such cases, we should be extremely cautious because we limit the capabilities of the tools that we’re using. We sacrifice automatic bundling of lazy-loaded chunks, type inference, and much more.