Flux in Depth. Store and Network Communication.

Edit · Jul 18, 2015 · 13 minutes read · Follow @mgechev

This is the second, and probably be the last, blog post of the series “Flux in Depth”. In the first post we did a quick overview of flux, took a look at the stateless, pure components, immutable data structures and component communication. This time, we’re going to introduce the store and how we can communicate with services through the network via HTTP, WebSocket or WebRTC. Since the flux architecture doesn’t define a way of communication with external services, here you can find my way of dealing with network communication. If you have any suggestions or opinions, do not hesitate to leave a comment.

Store

As we said, the UI in flux is built with pure components, which are (mostly) not holding any state. However, our application can’t be completely stateless. We have at least business data, UI state and an application configuration. The store is the place, which keeps this data.

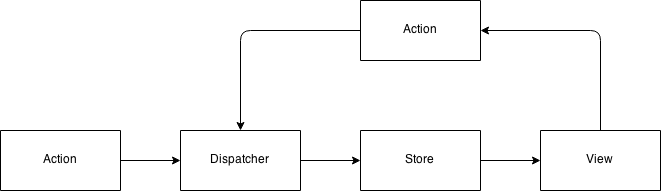

Lets peek at the flux data flow once again:

As we can see from the diagram above, the data flow starts in the view, goes to an action, which invokes the dispatcher, after that the store catches dispatcher’s event and in the end the data arrives in the view again. Alright, so the store is responsible for providing the data to the view. So far so good. How we can make the store deliver the required by the view data? Well, it can trigger an event! Recently observables are getting quite popular. For good or bad, they are going to be included in the JavaScript standard. If this makes you angry because you have to learn new things and JavaScript is getting fatter, you can find the guy who stays behind all of this here:

Observables are good way of building our store. If the view is able to observe the store for changes, it can update itself once the store updates. Lets take a look at the following design pattern (yeah, my friends already noticed I’m talking about design patterns constantly and did an intervention for me but didn’t help).

Chain of Responsibility

This is a design pattern, which is exclusively used in the event-driven programming. Lets change the context and talk about DOM for a while. I bet you know that you can listen for any event on the document, for example once a user clicks on a button the event will propagate to the root of the DOM tree (eventually, if nothing stop it) and be caught by your listener:

document.addEventListener('click', e => {

alert(`You actually clicked on element with #${e.target.getAttribute('id')}, not on document`);

alert(e.currentTarget === document)

}, false);

<button id="awesome-button">Click me</button>

If you click on the awesome-button, you’ll see two alert boxes: “You actually clicked on element with #awesome-button, not directly on document” and “true”. If you change the third parameter of addEventListener to true, the event will propagate in the opposite direction (i.e. from top to bottom, capturing mode).

Why I said all of this? Well, this is the pattern Chain of Responsibility:

In object-oriented design, the chain-of-responsibility pattern is a design pattern consisting of a source of command objects and a series of processing objects. Each processing object contains logic that defines the types of command objects that it can handle; the rest are passed to the next processing object in the chain. A mechanism also exists for adding new processing objects to the end of this chain.

Or if you’re have more enterprise taste, here is the UML class diagram of this design pattern:

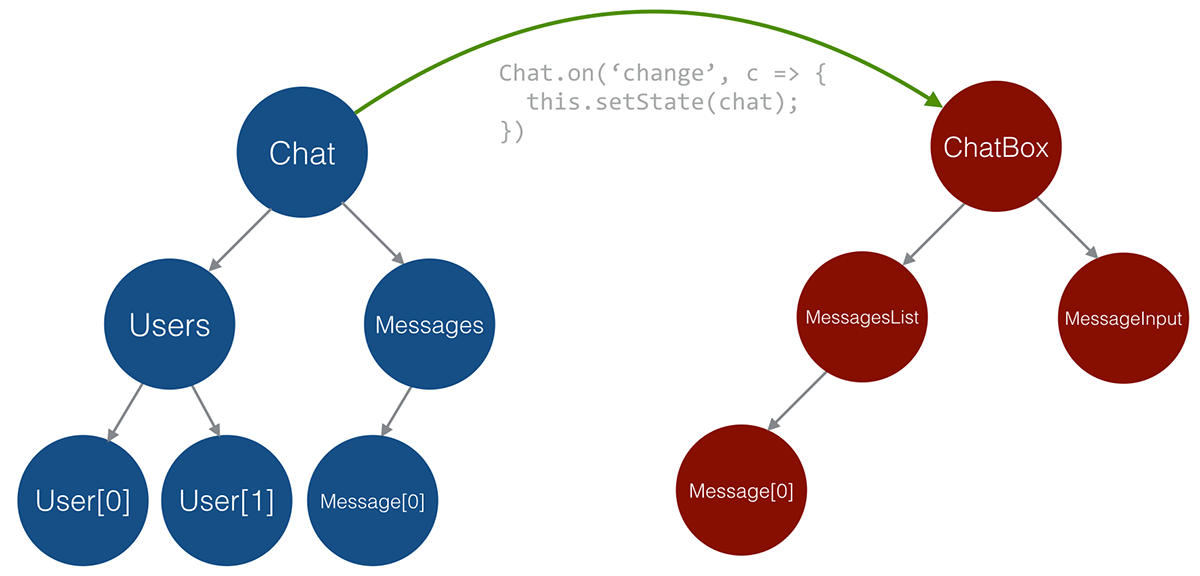

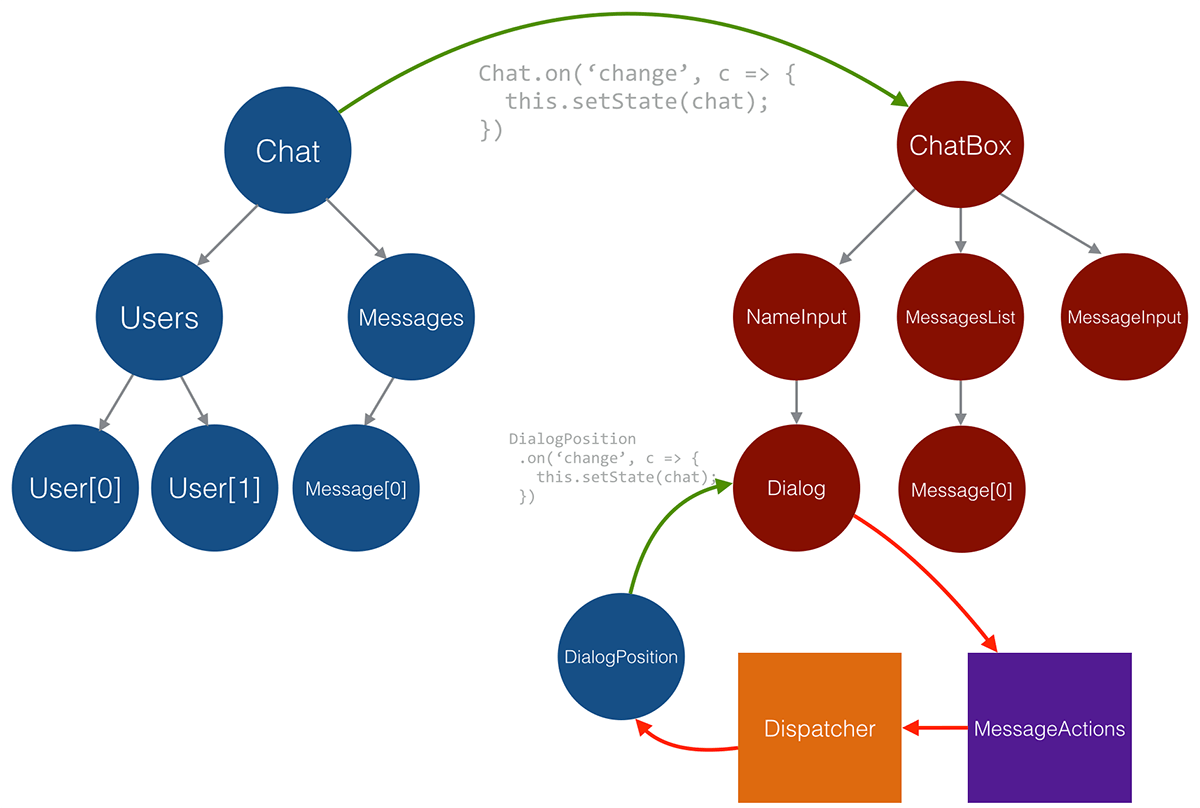

Why do we need Chain of Responsibility? Well, our store is a tree of objects, once a property in an internal node in the tree changes, it’ll propagate this change to the root. The root component in the view will listen for events triggered by the store object. Once it detects a change it’ll set its state. I’m sure it sounds weird and obfuscated, lets take a look at a diagram, which illustrates a simple chat application:

From the Store to the View

Lets take a look at the following diagram, it illustrates the initial setup of our application:

The tree on the left-hand side is the store, which serialized into JSON looks the following way:

{

"users": [

{ "name": "foo", "id": 1 },

{ "name": "bar", "id": 2 }

],

"messages": [

{ "text": "Hey foo", "by": 2, "timestamp": 1437147880686 }

]

}

The tree on the right-hand side is the component tree. We already described the component trees in the previous part. Here is a snippet, which shows the relation between the Chat store and the ChatBox component:

import React from 'react';

import Chat from '../store/Chat';

class ChatBox extends React.Component {

constructor(props) {

super(props);

Chat.on('change', c => {

this.setState(c);

});

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<MessagesList messages={this.state.messages}/>

<MessageInput/>

</div>

);

}

}

Basically, the root component (ChatBox) is subscribed to the change event of the Chat. When the Chat emits a change event, the ChatBox sets its state to be the current store and passes the store’s content down the component tree. That’s it.

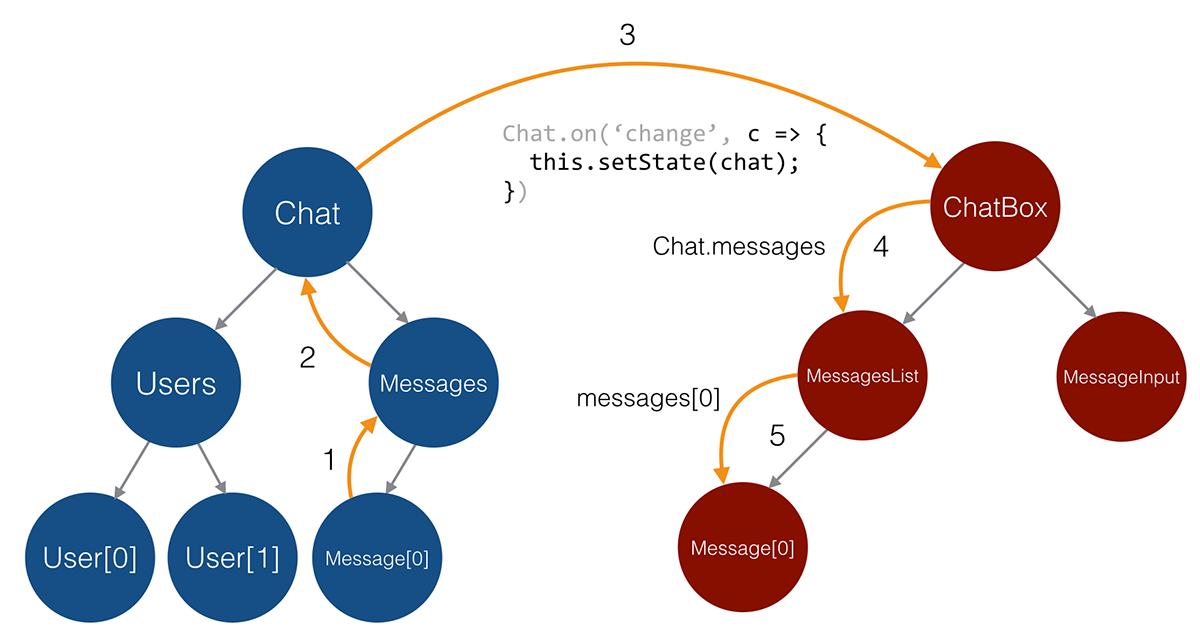

What happens if something change our store?

On the diagram above something changed the first message in the Chat store (lets say the text property was changed). Once a property in a message changes, the message emits an event and propagates it to the parent (step 1) which means that the event reaches the messages collection. The messages collection triggers change event and propagates the event to the chat (root object, step 2). The chat object emits a change event, which is being caught by the ChatBox component, which sets its state to the content of the store. That’s it…

In the next section, we’re going to take a look how the view can modify the store using Actions.

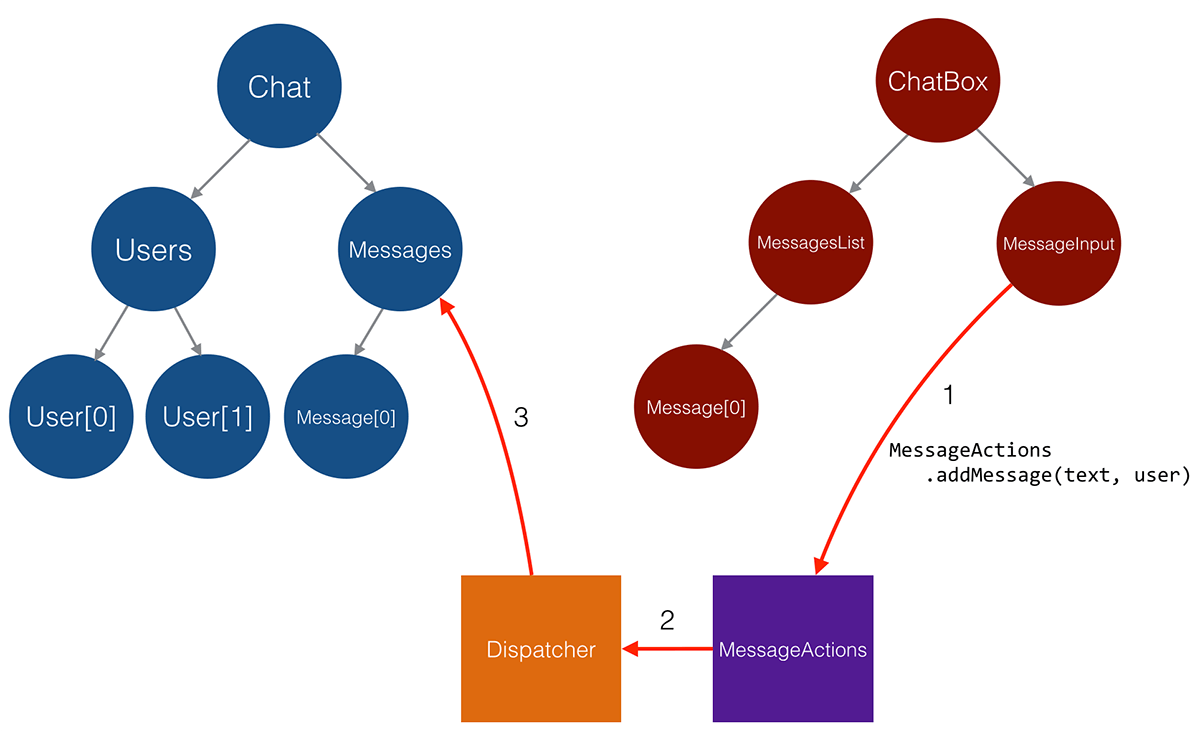

From the View to the Store

Now lets suppose the user enters a message and sends it. Inside a send handler, defined in MessageInput we invoke the action addMessage(text, user) the MessageActions object (step 1) (peek at the flux overview diagram above). The MessageActions explicitly invokes the Dispatcher (step 2), which throws an event. This event is being handled by the Messages component (step 3), which adds the message to the list of messages and triggers a change event. Now we’re going to the previous case - “Store to View”. All of this is better illustrated on the following diagram:

Model vs UI state

Most likely you’re building an application, which works on business data over given domain. For example, in our case we had:

- Messages

- Users

However, in most cases, this is not enough. Your application also has a UI state. For example, whether given dialog is opened or no, what is the dialog’s position, etc. The data, which defines now your components will be rendered, depends on both - your UI state and the model. This is the reason I create a combined store, which presents both. For example, if we add a few dialogs to our chat application, the JSON representation of the store may look like:

{

"users": [

{ "name": "foo", "id": 1 },

{ "name": "bar", "id": 2 }

],

"messages": [

{ "text": "Hey foo", "by": 2, "timestamp": 1437147880686}

],

"dialogsOpenStatus": {

"nicknameInput": true,

"editMessage": false

}

}

I always prefer to have separation between the UI state and the model because the communication with external services usually requires only handling changes in the model, so events emitted by the UI store does not concern us.

Quick FAQ:

Alright, I got it. So if I have a mouse move event, which changes the store by updating the mouse position, we should go through the entire described data flow?

This doesn’t seem like quite a good idea. If you have a big store and huge component tree, re-rendering it on mouse move will impact the performance of your application dramatically! What will be the biggest slowdown? Well, you’ll have to serialize the store to a POJO (Plain Old JavaScript Object), later you need to pass it to the root component, which is responsible for passing it down to its children and so on. And all of this because of two changed numbers? It is completely unnecessary. In such cases I’d recommend adding event listeners in the specific component, which depends on the mouse position and creating a separate store for it.

For example, if you’re using react-dnd in your application, the drag & drop component has its own state, which doesn’t have to be merged with the rest of the store. It can live independently. Let me show you what I mean on the following diagram:

In this example, when the store containing the dialog position updates it does not require update of the entire component tree.

How should I make my store trigger events?

The same way you did that in the dispatcher - use EventEmitter. Since we want to implement Chain of Responsibility, you will be required to keep reference to the object’s parent in order to propagate the event.

Remote Services

This is a hot topic. Most of the single-page applications require communication with services through a transport protocol, in order to fetch and store data. However, in the overview of flux there’s no such thing as TransportChannel, RemoteService or whatever. If there are involved a lot of different protocols (for example I’m working on a application, which communicates with other applications and services through HTTP, WebSocket and WebRTC data channel) it could get a bit hairy if you don’t create the proper abstractions.

In this section I’ll describe the basics of the network communication and later we’re going to discuss more interesting details.

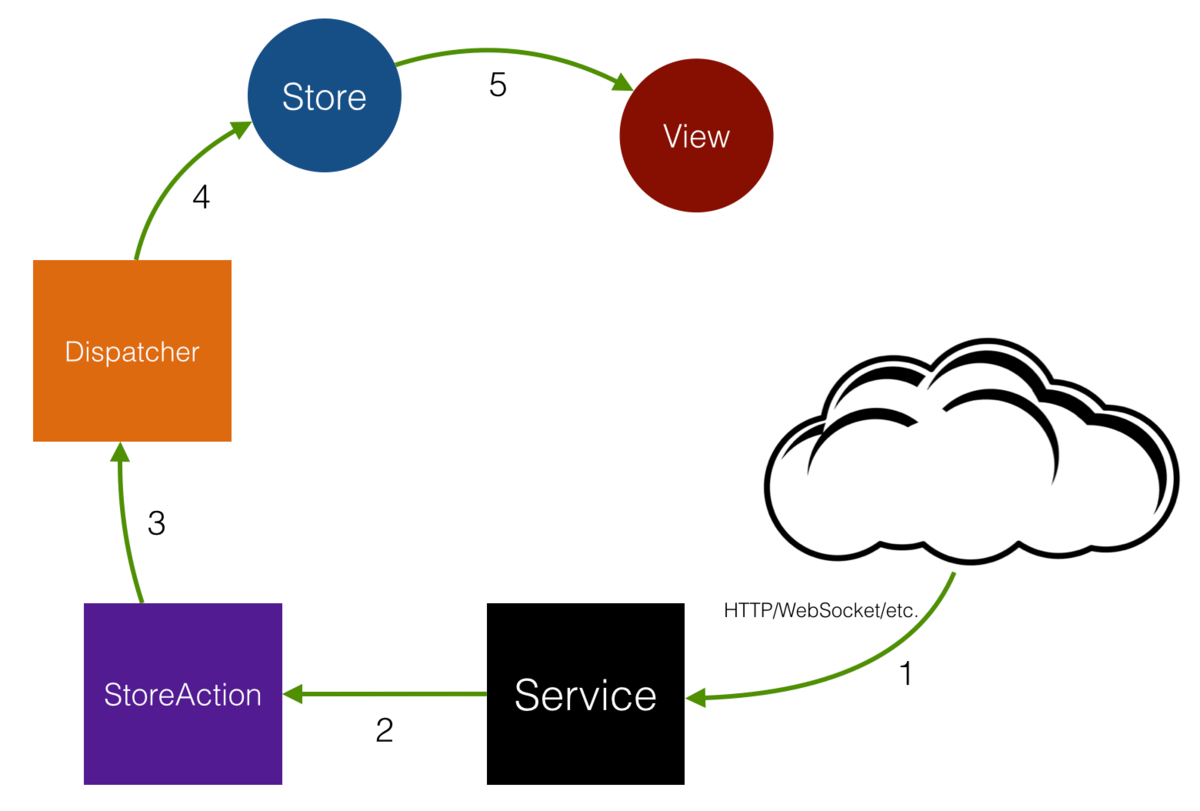

Alright, in the diagram which shows the overview of flux there is a “hanging” action. There’s no incoming arrow to the leftmost action but there’s outgoing one:

From the Network to the UI

We can use this “hanging” action in order to integrate the communication with the external services. Lets take a look at the following picture, in order to visualize basic communication with external service:

In it we can trace how a network event is being processed. The cloud is an external service/application. Initially we get a new message, it is being processed by the Service object (it is black on the diagram because it is like a black box for us right now, it may get quite complex depending on your application), later the semantics behind the received message is found and based on it, Service invokes a StoreAction. Now the flow goes exactly the way we described it earlier (From the Store to the View). We’re good for now. But what happens if the store changes? Nothing so far.

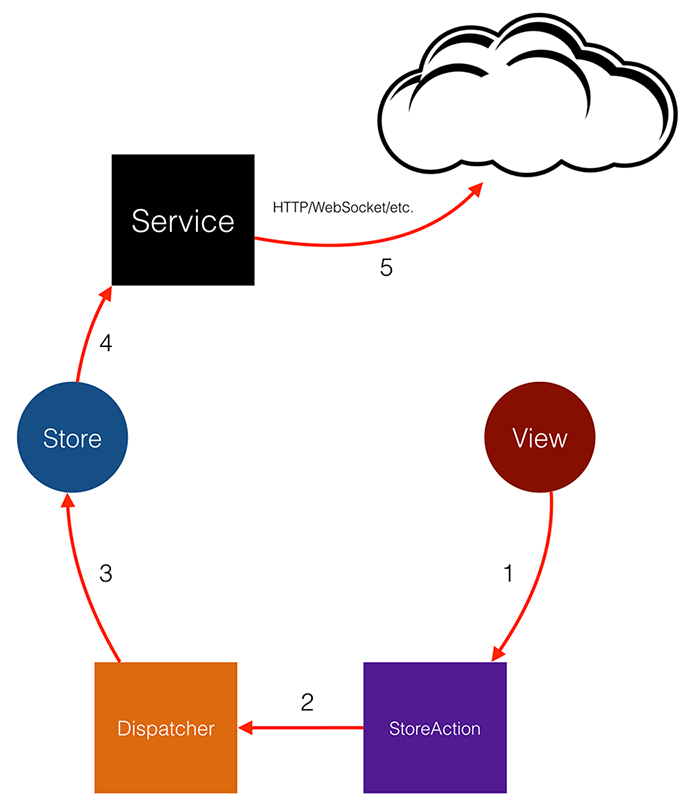

From the UI to the Network

In order to send network events based on changes of the store we can observe it and perform a specific action based on the change. Since it extends EventEmitter we can simply add on change handlers to the store inside the Service and this way we can easily handle all changes and process them:

But why the Service module shuld listen for store changes? Can’t it listen directly on the dispatcher? Most likely, in the store we’ll have some logic for handling the action passed by the dispatcher (for example format the raw data passed by the view). If the Service module listens for changes at the dispatcher we will duplicate this logic twice.

Everything looks good so far. But the Service module is still a huge black box. In the next section I’ll suggest a sample design of this module. If you don’t agree with something, have any questions or recommendations let me know.

The Service Module

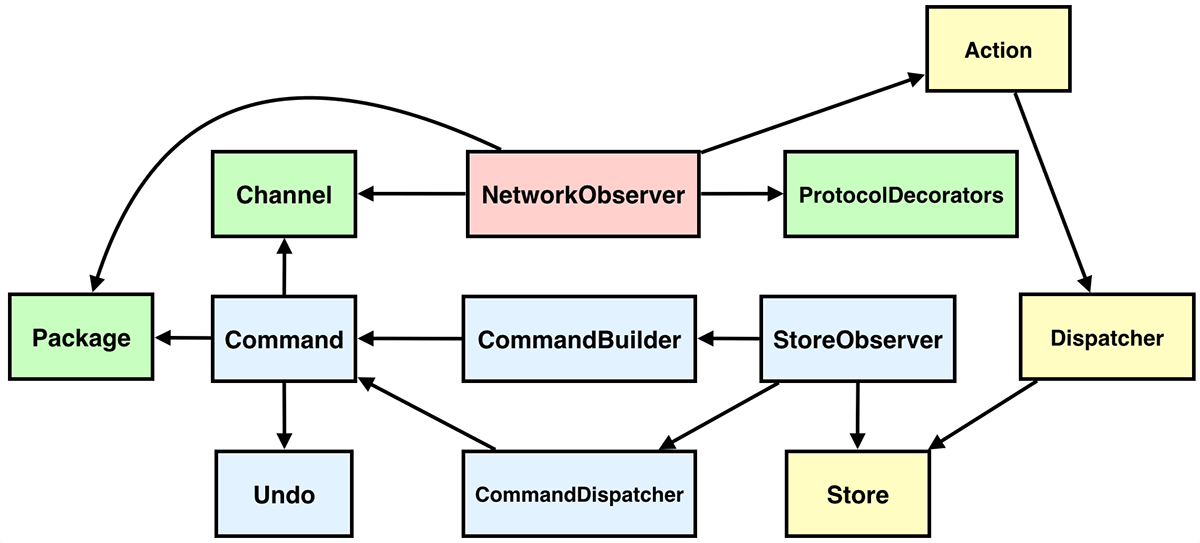

I was wondering whether to use UML for showing the components building the Service module, however I choose to make a colorful diagram like the one bellow:

There are a lot of boxes here. The yellow ones are part of the flux architecture. The blue ones are responsible for sending updates from the application to the remote service, the red ones are responsible for handling network events and the green ones are the intersection between the last two categories. One component could be implemented with a few classes, we’re not restricting ourselves to these components. We can think of them more like categories rather then specific classes. Here we’ll demonstrate a sample decomposition of the service module. Lets describe the most interesting components one by one.

Channel

Abstract channel. It could be extended by HTTPChannel, WebSocketChannel, WebRTCDataChannel, etc.

Package

The Package component represents the packages used by our protocol. There could be a hierarchy of package types. For example, if we build our protocol on top of JSON-RPC, we may want to extend the base Package class.

Command

Implements the Command design pattern.

CommandDispatcher

Responsible for dispatching commands. There’s one more link, which is not represented on the diagram - the CommandDispatcher owns reference to the Channel component. It checks whether the channel is open before sending the command, if it isn’t the CommandDispatcher retries after a given timeout. This component is also responsible for buffering commands, invoking their undo actions in case the command’s execution fails. The CommandDispatcher may implement different dispatching strategies:

- Request/response

- Sliding window technique

- Build a graph of the dependencies between the commands, process a topological sort and invoke the commands in the appropriate order

StoreObserver

The StoreObserver is responsible for handling change events of the store. Once it detects change in the store it creates a new command using the CommandBuilder and invokes it through the CommandDispatcher.

NetworkObserver

Waits for new messages emitted by the data Channel. This component is responsible for parsing the messages and processing them. Once the message is parsed, based on its content the NetworkObserver invokes specific Action.

Third-party Services

If you’re using a third-party service (Twilio for example) you can process in a similar fashion. You can create a wrapper of the service (in the case of Twilio, the Twilio global) and bring it in your flux data-flow.

Quick FAQ:

Isn’t NetworkObserver a “God class”?

Yep, it is. You can decompose it into a few smaller classes, same for CommandDispatcher where you can use the strategy pattern for dispatching the commands in the appropriate order.

What are these ProtocolDecorators?

Since we can create our protocol based on another, already existing protocol (JSON-RPC, BERT-RPC, etc.), we can process the incoming messages by using a chain of decorators. For example, we receive a basic string, next the JSONRPCDecorator can parse it to a valid JSON-RPC message and pass it to the next decorator (YourCustomProtocolDecorator), etc.

Can’t I get cascading updates when update the model? Can’t I reach a condition in which the view updates the store, it emits a change event, which is being handled by the Service module, which emits an event…etc.?

This can happen. There are two simple solutions:

- emit change event only when the value of given property is actually being changed

- emit

ui-changeevent when update the model from the view and emitserver-changeevent when change it from the server. The root component can listen for/change/events (yeah, this is a regex) and the server can listen forui-change.

I throw an event but a few stores are handling it?!

Most likely you have collision in the action types. I’d suggest to use the following schema for naming them: storename:action-name or something similar, which guarantees uniqness.

Conclusion

The first part of this post shown how we can wire the store with the view. The second part was about the basic idea of the network communication with external services. The last section described a sample implementation of the black box responsible for handling external messages, store changes, serialization of the store and sending it through the network. Although the first two parts were relatively canonical and predefined by flux, the last chapter was completely custom implementation. With it I wanted to imply that the micro-architecture we use (MVC, MVP, MVVM, flux, whatever) does not provide us the entire project design. It only puts some rules on how we should organize our application, defines the main building blocks and how we can wire them together, however, if we want to build a real-life application, most likely we’ll need to put some additional effort - the architecture or the framework won’t be able to solve all our concerns.